print preview

print previewback ROSS LOSAPIO

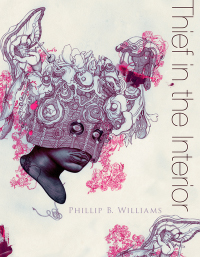

Review | Thief in the Interior, by Phillip B. Williams

Alice James Books, 2016

|

Phillip B. Williams’s Thief in the Interior calls out with the strong, passionate voice a debut collection of poetry needs, but also flexes a robust musculature. The poet displays profound ability in traditional form, as well as a talent for experimentation. His series of “Inheritance” poems and the long piece, “Witness”—two of the structural pillars around which the collection is built—innovate in ways that defy excerpting. They gracefully walk the line between convolution and intuition, and must be experienced as physical constructions on the page. This balance between tradition and liberation exemplifies Thief in the Interior, its poetry of surrender and defiance.

As Williams distorts and crafts the page, so does he warp time through his poems. In “Witness,” for example, the present moment stretches and bunches around the murder of nineteen-year-old Rashawn Brazell to a devastating effect. Following the example set forth by Mary Cornish’s poem “Fifteen Moving Parts,” the section “Witness: the duffel bag recalls dismemberment” opens by quickly casting its scene like a fistful of dice (“Once to the subway, twice to the recycling plant, / I was carried then emptied of my gift”), then unpacks each moment in dizzying detail:

Once to the subway, I was left near a trash bag by my carrier. When he held me,we didn’t speak to one another. I don’t know his story.

I was carried then emptied of everything I knew: hammer, flathead, monkeywrench toenail clipper, Bible against the cross of a tire iron, a knife for each Commandment.

Zeno’s paradox states that an arrow will travel half the distance between the archer and its target, then travel half the distance between that midpoint and the target, then half the remaining distance, over and over into infinity, never striking. Similarly, Williams’ work bifurcates time again and again, creating eternity from a single moment. Until the speaker attempts to enjoy an all-too-brief moment of pleasure, that is, as in “Do-rag”:

You don’t

like me but still invite me into your home

when your homies aren’t near

enough to hear us crash into each other

like hours.

Suddenly, time collapses on itself, sucking the moment’s joy into a singularity as the speaker reflects “ . . . I do not exist to you // outside this room” and another drawn-out moment of pain commences.

The silence that accompanies the violence in Thief in the Interior emerges from unexpected sources and unsettles the reader. We anticipate inaction from people—dismal though that sentiment may be—but when the natural and spiritual worlds offer no solace, it astounds, as in “Of Contour, of Cadence”:

Resist, don’t: the difference between what one thinks

the magnolias say—branches applauding

some animal act below—and what

they actually say . . . nothing

The effect surprises doubly, as the speaker takes such care in personifying the magnolias and other inanimate objects before stupefying them. Even the Almighty, as we see in “God as a Failed Figuration,” offers little by way of comfort. After a brief, impotent flash of lightning, the poem concludes, “From his weary blues / blues spill out but nothing around can / define how. Emptily, the blues signify.” Rather than meaning from nothing, we find nothing in meaning.

As duffel bags and magnolias attain person-like eminence, the human body degenerates, becomes little more than a container for the influence of others. “Watch boys be forced / into men,” “A Survey of Masculinity” commands, “by men who’ve forgotten their own / forcing.” Perpetuate and forget. If everyone hurts, then no one hurts. The broken logic of a fatally flawed value system infiltrates and spreads, as in “Apotheosis”:

Faggot was a thought

that snuck inside me, was put inside me,

and all the fields inside me turned Greek,

meaning tragic, meaning its beasts

were hybrid and hard to slay:

Perhaps we never truly slay these monsters—a task too daunting to ask of one hero—but Williams’ speaker survives and emerges from them, shedding wolf hide and guts in the collection’s final poem, “Birth of the Doppelgänger”:

My new self

bled out from the old self. I left

behind a husk pricked by daggers

of wood and lungs drunk off exhaust.

One imagines this rebirth might mirror the process of crafting Thief in the Interior—onerous self-assessment followed by creation.

Early in this collection, “Then as Proof the Land” begins, “Because when I write ‘tree’ I mean fire / of autumn.” That line break contains multitudes. The pause conjures burning destruction. When the eye drops to the next line, though, a small miracle occurs. The thought resolves itself, transforming flames into light filtered through a fall day. Philip B. Williams works this magic throughout Thief in the Interior, taking his reader past the brink of devastation—where many writers would safely pause, considering their task accomplished—into spiritual oblivion, and then lights upon some small, crucial piece of beauty. Thief in the Interior damns and redeems, and represents a truly worthwhile literary experience. ![]()

Phillip B. Williams is the author of Thief in the Interior (Alice James Book, 2016), Burn (YesYes Books, 2013), and the chapbook Bruised Gospels (Arts in Bloom Inc., 2011), which won BLOOM’s inaugural chapbook competition. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Callaloo, The Southern Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Sou’wester, and other journals. Williams has received fellowships from Cave Canem and a work-study scholarship in poetry from Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference. He is the poetry editor of the online journal Vinyl Poetry (YesYes Books).