print preview

print previewback ROSANNA OH

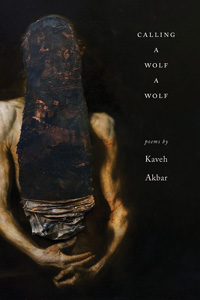

Review | Calling a Wolf a Wolf

Kaveh Akbar

Alice James Books, 2017

|

|

It’s the poet’s job to name things—that is, to not just assign, but invent a new language for that which is unprecedented. In the Bible, naming assumes world-making powers: we are told in Genesis that Adam named all the animals on earth in a single day. Kaveh Akbar performs a similar miracle with his utterly original debut collection, Calling a Wolf a Wolf, which won the 2018 Levis Reading Prize. After cataloguing the parts of what seems to be a garden, the poet-speaker writes in “Exciting the Canvas”:

On a gravel road, the soft tissues

of my eye detect a snake curling

around a tree branch. Because I am here

each of these things has a name.

If the world Akbar paints is a sort of paradise, then his speaker is a modern-day version of Adam, eager to discover and name all that it contains. Writing something into existence is to perform the supreme act of creation. But as in the story of the Fall, knowledge comes at a price.

Akbar’s poems acquaint us with his speaker’s plural selves—as an immigrant, alcoholic, man, child, son, lover, and artist. But their almost obsessive meditation on how language creates the self and vice versa unites them. In “Rimrock,” the speaker suggests that language is an idealized form of existence that can be inhabited:

Mostly I want to be letters—not

their sounds, but their shapes

on a page. It must be exhilarating

to be a symbol for everything at once:

the bone caught in a child’s windpipe,

the venom hiding in a snake’s jaw.

This idea that language can manifest the self constitutes the heart of the philosopher Walter Benjamin’s essay “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man.” According to Benjamin, naming demonstrates the capacity of language to convey “the mental being of man,” and he, too, alludes to name-making in Genesis. For Akbar’s speaker, then, writing is performative. “To be a symbol,” or to embody language, is to be as concrete as a “bone” or “venom” and threatens to inflict the same harm.

The first section of the collection presents a world so vast and new that the temptation to name nearly overwhelms the speaker. I am struck most by the intensity and purity of his pleasure, as though he were witnessing everything for the first time. The sight of the sunlit sky defies speech in “Do You Speak Persian?”: “Is there a vocabulary for this—one to make dailiness amplify / and not diminish wonder?” In “Desunt Nonnulla”: to learn “the names of things each new title a tiny seizure / of joy.”

Prayer for Akbar, who was born in Iran and grew up practicing Islam, is a means of naming oneself to God. In fact, to read Akbar’s poems—which, though confessional, do not slacken to autobiographical ramble—is to overhear a mind in passionate prayer. Over and over again, the speaker aspires to create a poetry in which the sacred and beautiful are one and the same. In “Learning to Pray,” a son takes pleasure in observing his father praying on a janamaz, even though he doesn’t understand the words:

I knew only that I wanted

to be like him,

that twilit stripe of father

mesmerizing as the bluewhite Iznik tile

hanging in our kitchen . . .

But there are limits to language. Prayers can go unanswered. Naming alone is not enough to realize the dream of communicating what Benjamin calls “mental being.” To “call a wolf a wolf” does not “dull its fangs.” The speaker is confronted with the realities of physical existence—his own body in particular, which he calls a “distraction.” In “An Apology,” he confesses:

Lord, I meant to be helpless, sex-

less as a comma . . .

Instead,

I charged into desire like a

tiger sprinting off the edge of

the world. . . .

Knowledge of violence and trauma haunts the speaker in “What Use is Knowing Anything If No One is Around”:

The spirit lives in between

the parts of a name. It is vulnerable only to silence

and forgetting. I am vulnerable to hammers, fire,

and any number of poisons. . . .

Here, the speaker positions his name in a dialectical relationship with the body, and the latter seems more immediate than the former. “Hammers,” “fire,” and “poisons” pose a danger more concrete than “silence” and “forgetting.” To understand the body’s hungers requires acknowledgement of one’s mortality.

Such truth is a premise in Akbar’s poems about alcoholism, where the speaker turns to drinking instead of God. And yet both the poet and alcoholic dwell in an elevated consciousness, and both are full of longing for spiritual absolution. “I do hope one day to be free of this body’s dry wood,” he writes in “Every Drunk Wants to Die Sober It’s How We Beat the Game.” Death, however, is not a means to an end so much as a “parable,” as he puts it in “Against Dying.” Knowing that he is sick, but also skeptical of his recovery, he asks: “how shall I live now / in the unexpected present.” The answer, I think, lies in the poem’s final lines: “I put a sugar cube / on my tongue and / swallow it like a pill.” The takeaway: life may be too addicting to not live.

How does the self—one that believes in art, grand design, and prayer—then navigate and reconcile itself to a world so full of cruelty and disorder? The question becomes even more fraught in the context of history, which provides examples of human cruelty that baffle Akbar. His poem “Palmyra” memorializes the Syrian archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad as a martyr for having spent a decades-long career devoted to preserving artifacts before his brutal execution by ISIS. In an interview with PBS, the poet explains that he couldn’t comprehend why a man would be killed for “preserving physical manifestations of human wonder and human awe.” In “Heritage,” which addresses a woman executed for killing her would-be rapist, the speaker concludes, “there is no solace in history.” The world is not the paradise he imagined. It’s an anxiety-provoking mess of contradictions that further remind him of his mortality.

Ultimately, redemption lies not within language, prayer, or the past, but in the speaker himself. In the last poem of the collection, “Portrait of the Alcoholic Stranded Alone on a Desert Island,” the speaker reaffirms his belief in God and the world, which holds a magical beauty he cannot deny:

Our father, who art in Heaven—always

just stepped out, while Earth,

the mother, everywheres around.

It all just means so intensely: bones

on the beach, calls from the bushes,

the scent of edible flowers

floating in from the horizon.

No longer is spirit at war with the body, as was elsewhere. Here, in another version of paradise, the speaker believes that heaven and earth can coexist like a “father” and “mother.” Here, he has discovered how to live in the unexpected moment by finding joy and meaning in his surroundings. Such a conclusion doesn’t rescue him from spiritual hunger; he acknowledges in the final lines that “The boat I am building / will never be done.” The poet’s labor is unending. But this truth does not convey despair as much as it does hope, for it offers a reason to keep going. ![]()

Contributor’s notes: Rosanna Oh

Contributor’s notes: Kaveh Akbar