print preview

print previewback WARWICK DEEPING

from The House of Adventure

British spellings retained

Editor’s Introduction

The novel’s protagonist, Paul Brent, aka Tom Beckett, aka Paul Renee, is an English soldier who, before serving in World War I, spent two years in English prison for fraud perpetrated against him by his now late wife and another man. After a shell explodes near Brent and his fellow soldier Tom Beckett at the French village of Beaucourt, Brent swaps identification disks with the deceased Beckett in hopes of starting a new life. (Viewers of Madmen will be familiar with a more recent use of this trope.) Brent (posing as Beckett) is soon after captured by the Germans. As a prisoner of war he aspires to learn French well enough to pass as a Frenchman. On his release, he takes the name Paul Renee and plans to explain his anglicized accent by having spent seven years living in England.

Influenza appears twice as a plot point of the novel; in both cases, it is the protagonist, Paul Brent, who is afflicted: his first illness comes just after his release from a German prison camp; his second after he has returned to Beaucourt where he meets again, and is ultimately bethrothed to Manon, a woman who loaned him a shovel to bury his friend just before she fled the bombed city. In both instances, the circumstances around his illness threaten to reveal his true identify.

|

|

| Smashed up Mill near St. Pierre Divion This shows a ruined brick-built watermill beside a fairly wide river, which is probably the Ancre. The vertical mill wheel has been exposed. Other ruined brick buildings are in the background. The photograph is attributed to John Warwick Brooke. St Pierre Divion, Beaumont-Hamel and Beaucourt-sur-Ancre were finally captured on 13th and 14th November, 1916 after four and a half months of heavy fighting and huge numbers of casualties. This action, sometimes called the 'Battle of Ancre', was part of the 1916 Somme offensive. [Original reads: 'OFFICIAL PHOTOGRAPH OF THE SOMME ADVANCE. By the side of the River Ancre. Ruins of Water Mill.'] Text and description courtesy The National Library of Scotland CC Attribution 4.0 | (444) D.574 -Permanent URL https://digital.nls.uk/74547404 |

|

Our excerpts here provide the narrative from the novel’s opening through the first illness. The second influenza plot point (not reprinted here in full) comes after Brent travels to nearby Amiens. On this return trip, he is in a cart with a man named Poupart and a talkative and intrusive older woman with whom he takes offense. Poupart raises the subject of influenza

“They had la grippe in the Louse where I have been staying; I expect I have caught it; I always do.”

“I have had la grippe thirteen times,” said the old lady triumphantly, leaning forward and looking across Paul at the pessimist.

“The thirteenth attack should have killed you, madame;” and, in a truculent aside, “you would never have had thirteen attacks if you had been my mother-in-law.’’

The old lady chattered to Paul all the way to Beaucourt. She was very inquisitive, and Paul was hard put to keep her curiosity within the limits of a decent reticence, for her old hands were ready to pull everything to pieces, even to interfere with her neighbours’ clothes.

On this return, however, whether exposed in town, or in the cart ride, it was Paul Brent who came down with la grippe for the second time.

Brent went down with influenza, an influenza of a particularly virulent type. He was alone in the house . . . and the disease struck Paul like a dose of poison. He was at work in the morning; that evening he was delirious, with a temperature that had soared.

In his delirium, his English phrases, muttered in front of a townsman, are taken, to Paul Brent’s peril, for German.

The influenza passages led us to this text for the 1918 Suite Coda, but what is at stake for the protagonist is so much enriched by the inclusion of the preliminary business of the exchange of identify, his secret, and his struggles and successes at a new beginning, that we err on the side a longer excerpt for greater context.

The photographs here from The National Library of Scotland show the kind of devastation the protagonist would have witnessed at Beaucourt and the surrounding region. Several notes set in the excerpted passages are those of Blackbird editors.

|

|

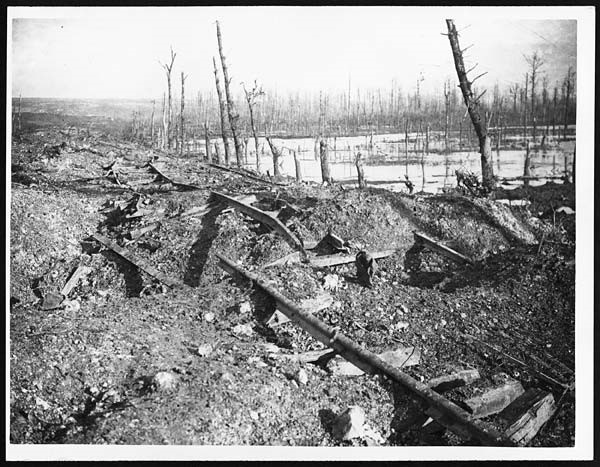

| The Railway Track at Beaucourt The shattered remains of a railway line extend into the distance. To the right lies the shattered and flooded remains of a small wood. The caption identifies this as the line at Beaucourt. This was near Beaumont Hamel, captured by the Allies in November, 1916, so the photograph was possibly taken at that time. In this photograph, John Warwick Brooke, the probable photographer, has here recorded the devastation of the civilian landscape and infrastructure of the area around the Somme.[Original reads: 'OFFICIAL PHOTOGRAPH TAKEN ON THE WESTERN FRONT. The railway track at Beaucourt.'] Description and photograph courtesy The National Library of Scotland CC Attribution 4.0 | (86) D.619 -Permanent URL https://digital.nls.uk/74547438 |

|

~

from Chapter I

Two stragglers lay sleeping in an orchard near the village of Beaucourt, sprawling upon a grass bank under the branches of an old apple tree. The sun had cleared the horizon and hung as a great yellow disc in the purple boughs of the beech trees on the other side of the stream. Overhead stretched the thin and cloudless blue of a March sky. The grass was silvered with hoar-frost and in the wood across the stream a bird was singing.

The men slept, two brown figures on the green bank. One sprawled on his back; the other lay curled on his side. Their boots were the colour of clay; so were their faces, the clay-coloured faces of men who had been starved, and who had fallen down to sleep the sleep of exhaustion. They were dirty with the dirt of five days’ fighting and foot-slogging. Their chins were painted black with a stubble of hair, and their noses looked pinched and thin. They had no greatcoats, no packs, no puttees, no equipment; nothing but a rifle, a blue water-bottle, and a haversack between them. At the world’s end a man gets rid of unnecessary lumber.

The dawn was extraordinarily still. There was not a sound to be heard save the singing of the bird in the wood on the other side of the stream. The country rolled into blue-grey distances under the level sunlight and the tranquil sky, a strangely peaceful landscape, the landscape of an unvexed and impersonal dawn. Beaucourt village slept in the sunlight on the slopes of its two hills. No smoke rose from the chimneys; no human sound came from it. Beaucourt was empty. The blue spire of its church and the gold vaned fleches of the chateau showed up against the purple heights of the Bois du Kenard.

The church clock struck six, six calm and level clangs that were quaintly challenging, almost ironical. From somewhere a long way off came the soft whoof of a gun, an English gun slewed round in some quiet orchard and firing a solitary shell or two into nothingness. There was a whine in the air, a whine that quickened over Beaucourt and became a menacing and snoring rush. The shell burst beyond the village, smashing an old apple tree and throwing up a great spurt of earth and smoke.

The man who had been sleeping curled up on his side, sat up and mopped the dirt out of his eyes, using his hands like the paws of a cat. A crack of lightning seemed to have broken the sky just above his head. The apple tree had been snapped off about three feet from the ground, and the splintered ends of the stump stood up like torn tendons.

The other sleeper was no longer a man, but a body. He was not recognizable, and from the ripped front of his tunic a red identity disc protruded, dangling pathetically at the end of a piece of frayed string.

756941 Pte. Beckett, T.

29 Fusiliers.

The live man looked dazed. War is an affair in which violent and absurd things happen, and men forget to be astonished. Moreover, Paul Brent was little more than a starved body, a dirty man sodden with a week’s weariness and moments of great excitement and blind fear.

“Tom’s dead.”

He uttered the words with the confidential and mumbling foolishness of a drunkard. It seemed quite natural that Tom should be dead. An immense apathy lay like so much stagnant water over the mud of Brent’s submerged emotions. He sat and stared and fingered the hair on his chin.

The man had been his comrade, his pal of pals, one of those rough-hewn, violent, warm-hearted creatures. They had fought together, drunk together, snuggled up close in the same barn or dug-out, shared their tobacco and a hole in the mud. Tom was dead, and yet if Brent was hurt by his death, it was a vague and animal pain, like the groanings of an empty belly.

He sat and stared.

His mouth felt dry.

He noticed that the water-bottle, rifle and haversack that lay between them had not been touched. He remembered that there was a little water left in the bottle, and he reached for it, drew the cork and drank. Some of the water dribbled down his dirty chin.

Brent put down the water-bottle, and groped in the right-hand pocket of his tunic. A few bits of broken biscuit resulted. He sat and munched them with sunken-eyed stolidity, alone in the midst of that extraordinary silence, and noticing how the sunlight glinted on the hobnails in Tom Beckett’s boots.

It was that dangling identity disc that gradually absorbed Brent’s attention, like a little luminous spot of light, a red blur in the fog of his exhaustion, a point of fire in his brain. It seemed to spread and to expand, and to change from a little red circle stamped with a man’s name to a picture, a picture of the man Beckett himself, of his vagabondage and his triumphs and all his boisterous good-humour. It seemed to challenge Brent, even made him unfasten his own tunic and produce the likeness of the thing the dead man wore, that little circle that was himself, the badge of a broken man and of the patchwork of a broken man’s career. It became a circle through which he looked at pictures, the pictures of that other life before the war, his boyhood, the silly tragedy of his marriage, his cynical success and his still more cynical failure, those moments of anguish and of shame, the bitter gibes that covered hidden wounds.

A look of spiritualized intelligence sharpened Brent’s face. His eyes ceased to be dead and listless. Something stirred in him, a passion to escape, perhaps a hunger for the finer things that had passed out of his life. The coarse-mouthed but most lovable man who lay dead there had taught him much the human fineness that mattered, those rough bits of courage or gentleness that make life something better than a selfish scramble. For Beckett had been a vagabond with a religion of his own, a homeless man, a childless man, and yet in his way a sort of savage Walt Whitman, finding life good and wholesome and free.

Brent sat and faced it out. Watching beside his dead friend in the early sunlight of that spring morning, he saw himself as the shabby failure that he was, a man who had accepted spiritual bankruptcy with the cynical apathy of a tramp who leaves his self-respect and his citizenship in some convenient ditch. Acceptance! It was just that blind and drifting attitude that had doomed him, while Beckett the adventurer had punched his way towards a rude religion.

In that most singular and prophetic moment of his life Paul Brent had his vision of non-acceptance. He saw the gap in the wall and leapt through it, feeling that the dead man was offering him his chance. The burly audacity of the thing would have drawn a laugh and an approving punch on the chest from the man who lay dead. Beckett had no wife, no children, no woman who would be hurt. Brent thought of all that before he made his choice.

There was an element of solemnity and of reverence in Paul Brent’s carrying out of that interchange of identities. He unfastened his own disc, and that solitary one of Beckett’s. He felt in his dead friend’s pockets and sorted out his possessions, a complex that included his pay-book, a pipe, some odd buttons, ten francs and fifty centimes in money, an English penny, a stubby pencil and a couple of dirty picture postcards, a hank of string and a few matches. Brent tied Beckett’s identity disc to his own braces, and put the dead man’s pay-book in his pocket. His own disc he fastened to the body and left the pay-book lying upon the grass.

Then the last comradely act suggested itself, and it stirred Brent to vague emotion and a softening of his red-lidded eyes. He picked up the rifle, shouldered it, and walked up the hill to Beaucourt village in search of a pick and a spade.

As he walked up between the orchards a strange calmness fell upon him, a calmness that was neither apathy nor indifference. He became conscious of the beauty of the morning, and of the more tragic beauty of this French village with its red roofs and its red and white walls showing vividly against the purple of the Bois du Renard. Beaucourt was on the altar of sacrifice. Brent entered it by the little Rue de Rosieres, and he saw things in Beaucourt that he would never forget. It was like a woman bereft of her children, standing dazed, with blind eyes and open mouth. It was as though it could not believe that the thing had happened on that soft day in the coming of the spring.

The doors of nearly all the little houses and cottages were open, so that Brent could see into the lower rooms. A gallery of pictures, impressions of a silent tragedy! Rooms full of a tumult of escape and of little treasures searched for, snatched up and carried away out of a world of disorder. Floors littered with clothes, papers, bed-linen, furniture. Chests of drawers and cupboards standing open. The last meal left upon a table, dirty plates, bottles, the chairs pushed back as the people had left them.

In one cottage Brent had a glimpse of a woman’s night-dress and a little black hat trimmed with red ribbon hanging on the post of a bed. An open window gave him a glimpse of a child’s cot with the clothes thrown back and one pink sock left lying. Beaucourt would have hurt the heart of a cynic. At the corner where the Rue de Rosieres joined the Rue de Picardie a melancholy and forlorn brown dog came nosing up to Brent and followed at his heels.

Brent petted the beast.

“You poor old devil.”

He paused outside the Cafe de la Victoire ironical yet prophetic name! It was a long, two-storied, lovable old house in red brick, set back beyond a raised path of grey, squared stones, and looking with its dormer windows into the orchard and garden of the big stone house across the way. The green shutters hung open. A lace curtain fluttered from one of the windows. Brent knew the Cafe de la Victoire; for he and Tom Beckett had drunk red wine there.

Paul did not enter the house, but scrambled up on to the raised path and pushed through a blue door in the stone wall surrounding the garden. There were pollarded lines beyond the wall, and a quaint bosky path ran between the rows of trees. Brent followed the path, knowing that it would bring him to the yard at the back of the house, and that he might find what he needed in one of the sheds.

|

|

| Wrecked Houses This image captures some of the devastation at Irles. The brick house or houses shown here have been irreparably damaged, most probably by shellfire. Sadly, this was an all too familiar scene at the time. Countless towns and villages close to the Front were completely destroyed as a direct result of the fighting. Although no date is give, it is possible this photograph was taken in 1917. Irles was successfully captured by the Allies on 10 March 1917, during the Allied Spring Offensive. The Allies' advance ultimately forced the German Army to retreat towards the Hindenburg Line. [Original reads: 'OFFICIAL PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN ON THE BRITISH WESTERN FRONT. SCENE IN IRLES. Wrecked houses.'] Description and photograph courtesy The National Library of Scotland CC Attribution 4.0 | (27) D.1041 -Permanent URL https://digital.nls.uk/74548388 |

|

~

[In Chapter II Brent comes upon the ruined café’s owner, Manon, and is able to communicate that he needs her spade to bury a fellow soldier; she has just buried her valuables near a brick wall. Not only does he not plunder the site, he arranges bricks and rocks around her attempted safekeeping to further obscure signs of recent digging. When he later returns to the village, it is this honesty that leads Manon to trust him in his offer to help her rebuild her ruined home and business, and they are eventually betrothed.

After Manon has given him her tools, and is on the road away from the bombed village, he goes, exhausted, to bury the body of his friend, but is discovered by equally spent German soldiers who quietly help him finish the burial, give him bread, and then take him as a prisoner of war.]

~

from Chapter III

So Brent went as a prisoner to Germany, and was catalogued as “Number 756941 Pte. Beckett, T”; and Paul Brent’s name appeared among the “missing,” a casualty that was corrected a few weeks later to “killed.”

Paul Brent was a prisoner, but he had escaped, escaped from the tradition of blond hair and a thin mouth, Turkey carpets and a three-tiered cake-stand, and the memory of the greedy nostrils of a thoroughly respectable but wholly unprincipled woman.* He was free, even while he sat and peeled potatoes in a prison hut, washed his one shirt, or slept square-backed on his bed of boards. A sense of liberty soaked into him. He saw a new sun, a new horizon, new stars, a sportsman’s chance, a renewal of that great adventure. His manhood tightened his belt, and discovered itself in better condition, despite its thirty-seven odd years and an incipient plumpness about the waist. That plumpness had disappeared in France and Belgium, and Brent’s mental flabbiness followed it out of the German prison camp.

* a reference to Paul Brent’s late wife whose betrayal was the cause of his two years in prison.

Brent happened to be in a “mixed camp” for the first few months, and he set himself to learn French. He attacked it with such fierceness and assiduity that Alphonse, his pedagogue, a French waiter with a family in Soho, accused him of being in love. It was a crude accusation, and Brent demolished it.

“I finished with that five years ago.”

“No nice little French girl, Mister Beckett?”

“Not even a mam’selle. I want to be able to earn more money. Business just business.”

“I fall in love every month,” said Alphonse; “it is good for my digestion.”

“And Madame’s temper?”

“Oh, that is an affair apart,” said Alphonse; “there is no woman like my Josephine. It is quite different. She mends my socks, and sees that I have a clean collar. She has but to say ‘Alphonse’ and I would leave all the beauties of the Sultan’s harem and carry her umbrella. It is the woman that mends one’s socks who matters.”

“I suppose so,” said Paul; “mine didn’t.”

But he became quite a creditable Frenchman, even picking up the slang and the atmosphere of the language, and teaching himself to think in French. His accent was not too English. “Bong” and “Bo-koop” ceased from his vocabulary. He learnt to imitate all Alphonse’s tricks, his little mannerisms, his expressive silences, the way he talked with his shoulders, hands, and even with his legs and buttons. Alphonse was a southerner, and gaillard.

He did not merely converse; he was an amateur dramatic society in a shabby uniform of French blue.

Then the War ended, like a machine of which someone has forgotten to turn the handle. Brent happened to have been moved into Belgium about three weeks before the Armistice, and the coincidence rhymed with the idea he had in his head. Strange things happened one wet night in that particular prisoners’ camp. There were rumours, a panic, an explosion, a joyous scramble in the office of an alarmed and fugitive commandant. Someone discovered the official pay-box. German notes, wads of them, were tucked into tunic pockets, and Brent was one of those who came by a quite respectable handful.

*****

It was in a Belgian village on the road between Dinant and Philipville that Paul met the first English troops he had seen, a battalion that was settling into billets on its long march to the Rhine. Brent was sludging along a lane, a dirty grey sock showing through the toe of his right boot, all his worldly gear in a German sandbag slung over his shoulder. He had a vile headache, little prickles of heat and shivers of cold chasing each other up and down his back. He had not shaved for a week, and his great-coat was all mud.

“Hallo, chum!”

Behind the outswung black door of a stable Brent saw a field-cooker in steaming fettle, and a couple of cooks hard at work. One of them was mopping out a camp-kettle with a handful of grass. An exquisite smell of hot stew wasted itself on Brent’s nostrils.

“Got any tea?”

The cook dropped his camp-kettle, and went and laid hold of Brent.

“Here chum hold up! You come and sit down. Been in Germany, what?”

“Yes Germany,” said Paul.

They sat him down on a ration box, but he flopped like a sackful of old clothes, and the sympathetic one had to act as a buttress.

“You’re done in, chum. Give us some of that stew in my mess-tin, Harry.”

But the sight and the smell of the stew made Brent feel sick. The cook held his head like a mother, and Brent’s head felt dry and hot.

“You want the doc, chum; that’s what’s the matter with you. Ten days in hospital in a real bed, between real sheets, with a lovely little nurse feeding you with a spoon.”

Brent protested, gripping the cook’s wrist.

“I don’t want the doc, old chap. I’m done up, that’s all. I’d like a cup of tea, and a ration biscuit.”

“Rot,” said the cook, “you’re ill.”

One of the company stretcher-bearers happened to pass that way.

“Hi Chucker, where’s the M.O.?”

“Headquarters mess.”

“Run along and tell him there’s a returned prisoner here; he’s sick.”

“Right-oh,” said Chucker; and he went.

The battalion doctor came back with the stretcher-bearer, feeling aggrieved that he should be dragged out at the end of a day’s march to see some casual devil who did not belong to his own crowd. Human nature is like that, and this doctor boy was unripe and insolent.

“Hallo, what’s the matter with you?”

Brent was crouching on the box, holding his head between his hands.

“Headache, sir.”

The M.O. looked at him, brought out a thermometer, glanced at the mercury and gave the glass tube a sharp flick.

“Under your tongue. Don’t bite it.”

The sympathetic cook was damning the doctor with a pair of truculent blue eyes, eyes that said “You blighter I’d like to punch your jaw.” But the officer was not sensitive to psychical impressions; he had left a game of “Slippery Sam,” and he felt Brent’s pulse while Brent sat and sucked the thermometer with an air of vacant helplessness. The glass tube was tweaked out of his mouth, glanced at, and put back in its metal case.

“Hospital for you, boy.”

Brent looked scared. He did not want to go to hospital.

“I’m just done in, sir. I’ll be all right to-morrow.”

“Will you!” said the doctor tensely, pulling out a note-book and beginning to scribble, resting his foot on Brent’s box, and the note-book on his knee.

“Name and number?”

“I don’t want to go to hospital, sir.”

“Don’t argue. Name and number?”

“No. 756941 Pte. Beckett, T.” said Brent.

“Unit?”

“2-9th Fusiliers.”

“Bring him along to the medical inspection room, will you? Street by the church.”

The doctor snapped the black elastic round his note-book and walked off.

“He ought to be boiled in muck,” said the cook.

Five minutes later this sympathetic and expressive soul made a dash down the road after a figure in a muddy greatcoat, a figure that had sneaked out of the cook-house with a staggering determination to escape. Brent collapsed under a hedge outside a cottage, lying face down-wards in the mud. His temperature was 104.7.

“What did you do it for, chum?”

Brent could not explain. He had fainted.

A field ambulance car collected Paul Brent and carried him off to another village where he lay in a barn for half an hour, flushed and torpid, yet resenting the efforts of an orderly to make him drink hot cocoa. An officer came and examined him, a very quiet man with a big fair moustache and intelligent eyes. Ten minutes later Brent was put on a stretcher in one of the big Daimlers, with a card in a brown envelope fastened to one of the buttons of his greatcoat; there were two other patients in the car. The quiet officer climbed in and assured himself that Brent was well covered with blankets.

“Feel warm enough?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Don’t you worry. You’ll soon be comfortable.”

The officer’s voice made Brent do an absurd thing; he turned his face towards the canvas, and wept.

The car left its sick men at a casualty clearing station in Charleroi.* Brent had a vague impression of a great red brick building glooming up into the murk of a winter night, of boots clattering on tiled floors, of many voices, and of people who would keep moving about. He was irritable, a blazing mass of physical discomfort, slipping over the edge of sanity into delirium. Two orderlies came and carried his stretcher into a ward. He was laid on a bed, and two other orderlies started to undress him.

* British Casualty Clearing Station #20 was at eight previous locations before ending at Charleroi from November 1918–August 1919.

Brent was struggling to get at something that was buttoned up in the right breast pocket of his tunic. The orderlies were trying to remove the tunic, and Brent began to fight.

“All right, old chap, all right!”

“Here, leave that alone.”

“What’s the matter?”

“I want my money.”

“You can’t have money in hospital.”

“B——y hell, —give me——”

“Let him have it,” said the elder of the two orderlies; “let the poor blighter have it. Shove it under his pillow.”

“All right, old chap.”

Brent calmed down like a child, but the nurse in charge had heard the scrimmage, and came sailing up in her grey dress edged with red. She was a fair-haired, hard-faced woman, with thin, clean-cut features, her eyes set too close together, and little irritable lines crimping her mouth.

“What’s all this noise?”

Then a strange thing happened to Brent. He sat up in the bed, staring at the woman with eyes of anger and of horror.

“What’s she doing here? Take her away, take her away, or I’ll—I’ll cut her blasted throat!”

The nurse screwed up her eyes at him, and backed away.

“He’s delirious,” said one of the orderlies; “lie down, old chap.”

Brent made a sort of futile grab in the direction of the nurse.

“Let me . . . She’s a devil!”

The nurse walked away down the ward with the detached dignity of a woman whose professional soul moved calmly through the world of sickness and of words, and Brent fell back on his pillows.

“What’s she doing here,” he kept saying; “why can’t they let me alone?”

Paul Brent came very near death in that hospital at Charleroi. Influenza passed into broncho-pneumonia, and for days he lay there in a quiet stupor with bluish lips and a grey face. He was just so much pulp, not caring whether he lived or whether he died, and capable of but two semi-intelligent mental reflexes, the turning of his face to the wall when the yellow-haired nurse came near, and the insinuating of a flabby hand under his pillow to make sure that those German notes were there. He occupied a corner bed, and sometimes there was a red screen round it. His neighbour in the next bed nicknamed him “Arthur,” and told everybody that he was “a bit balmy.”

But Brent’s illness passed, and he lay there hour by hour, watching life, and beginning to react and to think.

He saw the high, bare, yellow walls, the rows of beds with red quilts, the scrubbed floor, the canvas-shoed orderlies, the nurse, the doctor with “gig-lamps” and a bald head, the other men who dozed and chattered, or read magazines and books and letters from home. Some of the men wrote letters, and Brent’s neighbour offered him a field postcard.

“What about the missis, Arthur?”

“Haven’t got one,” said Brent.

The red screen annoyed him. There was something irritating in the colour, a vague suggestion of officialdom, red tape, tyranny. Brent asked to have it taken away. He spent most of his time staring straight up at the ceiling, and at a black smudge of cobweb in the corner where the chimney jutted out. The dirty whiteness of the ceiling was restful; he saw pictures on it, pictures that helped him to think. There was no pattern on the ceiling; it was like a fresh sheet, a clean piece of canvas upon which Brent could paint what he pleased; and lying through those long days he worked out his pictures on the plaster, and underneath them was written the word, “Escape.”

He realized that he would have to lose himself again, for the Machine had reclaimed him and would pass him with stupid efficiency on its Trucker system to some place where he would be sorted out and railed back to England. He began to live in fear of being recognized by some chance friend. Even the blond-haired nurse’s absurd likeness to that other woman who had died in England still roused in Brent an elemental antipathy and a fierce alarm.

He sulked, and turned over into the blind corner when-ever she came near his bed.

“What is the matter to-day, Beckett?”

Her voice was an echo of that other woman’s voice, a metallic voice that attacked. Brent’s back remained churlishly on the defensive.

“Don’t want to be bothered that’s all”

~

from Chapter IV

Beckett was convalescent, and as his strength returned, his restlessness returned with it. He was allowed out in the hospital grounds, where he trudged about with the idea of getting himself fit, and feeling like an animal in a cage, and always afraid of meeting some disastrously in-opportune friend. He had glimpses of Charleroi, that hack and gray mining town with its slag-heaps and smoke and its air of shabby sumptuousness. There were women in Charleroi, swarthy little Belgian women, shops full of luxurious things at luxurious prices, the glitter of jewellery, the glare of electric light, Belgian flags, trams, red wine, pavements where a man could loiter and catch the smell of fleur-de-trefle in a woman’s clothes. Charleroi made one think of the sallow face, the lowering cloth cap, and the sexual swagger of an apache.*

* apparently a reference to a member of a French street gang, Les Apaches. Later in the novel Brent will joke with a shopkeeper, upon buying a pair of brown velvet trousers. “I am to be an apache, madame. A pair of velveteen breeches. What next?”

“Escape” was written on Brent’s heart; and he had staged the first act of the adventure at Charleroi. He knew that the day of his discharge was drawing near, and he might expect to find himself handed to some casual R.T.O. who would pass him down the line to his base-depot, and Brent had decided that he must vanish before such a thing could happen. He did not want to go back to England. He was thoroughly determined that he would never recross the Channel.

Early in January he received the final stimulus that shocked him into immediate action. He was wandering about the hospital grounds when he saw a little officer with a florid and familiar face limping down the path between the plane trees. Brent was caught off his guard.

He stared, and then swung round on one heel, but the officer boy stopped.

“Hallo; isn’t it Brent? You were in my platoon?”

Brent had to face it out.

“So I was, sir.”

“I got knocked out just before the retreat. What happened to you?”

“Prisoner,” said Brent.

“Been sick, have you?”

“Flu, sir, and pneumonia. I’m all right now. I expect to be discharged in a day or two.”

The officer boy shook Brent’s hand, feeling himself half a civilian and on the edge of demobilization. Besides, Brent had always been a gentlemanly chap.

“Well, good luck.”

“Good luck to you, sir,” said Brent.

That incident gave the necessary flick to his decision. Men who were ripe for discharge were allowed out on pass into Charleroi, and Brent got his pass that evening; it was dated for the following day. The N.C.O. in charge of the convalescent “wing” was a far more human person than the yellow-haired nurse.

So Paul Brent went down into Charleroi on a grey January morning, with the thrill of an adventure in his blood. He had scrounged a couple of tins of bully beef and a pocketful of biscuits, his reserve ration for the road. “Escape” was in the air. The trams clanged it, the shops were ready to help in the conspiracy: the crowded streets made Brent think of a dirty, commercialized but fascinating Baghdad. He began to feel himself part of this continental crowd and no English soldier numbered and labelled for an immediate return to some niche in that damned temple of Monotony, the Industrialism of England. He was a little Haroun al Raschid wandering as he pleased in this city of adventures. ![]()