print preview

print previewback E.W. GIBSON

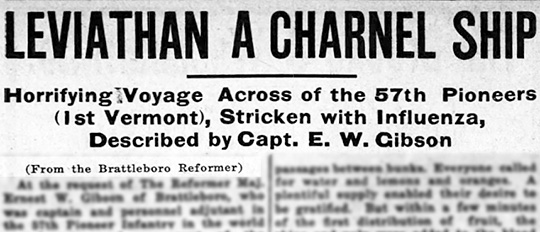

Leviathan A Charnel Ship

Horrifying Voyage Across of the 57th Pioneers

(1st Vermont),

Stricken with Influenza,

from The Bethel Courier, February 19, 1920; credited there to the Bratteboro Reformer; images are collected from digital archives and are believed to be in the public domain.

|

|

| “Leviathan A Charnel Ship” headline from The Bethel Courier, February 19, 1920. | |

At the request of The Reformer Maj. Ernest W. Gibson of Brattleboro, who was captain and personnel adjutant in the 57th Pioneer Infantry in the world war, has prepared an account of the regiment’s trip across the Atlantic to France on the big steamer Leviathan, on which, were many Brattleboro young men, especially with reference to the conditions which prevailed as a result of influenza. His account of the trip, in which are incorporated extracts from an official report, brings out some horrible conditions which the public has little realized. Every Vermonter should read in its entirety Major Gibson’s story, which follows:—

In February, 1918, the First Vermont Infantry, which had been wrecked by the short sighted and entirely wrong policy of the war department, was given the new name of the 57th Pioneer Infantry. The remains of the broken National Guard organizations of New England and New York were re-designated as Corps and Army Troops, assembled at Camp Wadsworth, there filled up with drafted men and sent overseas.

| “The victims of the epidemic fell on either side of the road unable to carry their heavy packs.” | |

The 57th Pioneer Infantry had about 50 commissioned officers and 450 noncommissioned officers from Vermont. These were men who had clung to the old organization with a fine sense of loyalty to their state. The other commissioned officers of the regiment as finally completed came from the National Guard regiments of many states. The balance of the enlisted personnel came from Philadelphia, Chicago, and from Tennessee. On the sixth day of September, 1918, about 3,000 men from Tennessee were called into service. They came from the cities and villages, off the cotton plantations and from the mountain homes of that state. These boys were a home loving, God fearing lot of men. To many the trip to camp was a first experience on a railway train. Twenty-five hundred of them were assigned to our regiment on the 12th day of September. They were equipped, inoculated, vaccinated and on the 23rd day of September, 11 days after coming to the regiment, started on the long trip to France. At Camp Merritt we stopped long enough to secure equipment to conform to the overseas standard, so far as available, and drop such men as were undesirable. We were assigned to sail on the giant Leviathan, then moored at her pier in Hoboken.

The first battalion assigned to guard duty aboard the troopship moved out from camp about 1 o’clock on the morning of the 28th of September. The second and third battalions marched out from their barracks about 1 a.m. on the morning of the 29th of September. We had proceeded but a short distance when it was discovered that men were falling out of ranks, unable to keep up. The attention of the commanding officer was called to the situation. The column was halted, the camp surgeon was summoned, the medical examination showed that the dreaded influenza had hit us. Although many men had fallen out we were ordered to resume the march. We went forward up and up over that winding moonlit road leading to Alpine Landing on the Hudson, where ferry boats were waiting to take us to Hoboken.

|

|

| USS Leviathan Troops on board the transport, 1918. All appear to be wearing life jackets. Note the men seated on cargo booms. View looks forward and to starboard from the ship’s port bridge wing. Photograph by Zimmer. Photograph and description courtesty of the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command. |

|

|

|

USS Leviathan, 1918 (detail) |

|

The victims of the epidemic fell on either side of the road, unable to carry their heavy packs. Some threw their equipment away and with determination tried to keep up with their comrades. Army trucks and ambulances following picked up those who had fallen and took them back to the camp hospital. How many men or how much equipment we lost on the march has never been determined.

On board the transport men continued to be stricken and 100 of these were taken off and returned to shore before sailing. On Sunday afternoon, the 29th, tugs pulled the great ship into midstream, turned her prow in the direction of open ocean, the great propellers began to turn and we were off to the Great Adventure.

| “The decks became wet and slippery, groans and cries of the terrified added to the confusion of the applicants clamoring for treatment . . .” | |

We had on board 9,033 officers and men and about 200 army nurses on their way to hospitals in France. The presence of the nurses was very fortunate as it afterwards turned out. The ship was packed, conditions were such that the influenza bacillus could breed and multiply with extraordinary swiftness. We were much of the way without convoy. The U-boat menace made it necessary to keep every port hole closed at night, and the air below decks, where the men slept, was hot and heavy. The number of sick increased rapidly. Washington was appraised of the situation, but the call for men for the allied armies was so great that we must go on at any cost. The sick bay became overcrowded and it became necessary to evacuate the greater portion of E deck and turn that into sick quarters. Doctors and nurses were stricken. Every available doctor and nurse was utilized to the limit of endurance. The official report of the medical officer to the commanding officer made Oct. 11, 1918, on file with the war department, is a correct and interesting account of the conditions. It follows in part:—

There are no means of knowing the actual number of sick at any one time, but it is estimated that fully 700 cases had developed by night of September 30. They were brought to the sick bay from all parts of the ship, in a continuous stream, only to be turned away because all beds were occupied. Most of them lay down on the decks, inside and out, and made no effort to reach the compartment where they belong. In fact, practically no one had the slightest idea where he did belong, and he left his blankets, clothing, kit, and all his possessions to be salvaged at the end of the voyage.

|

|

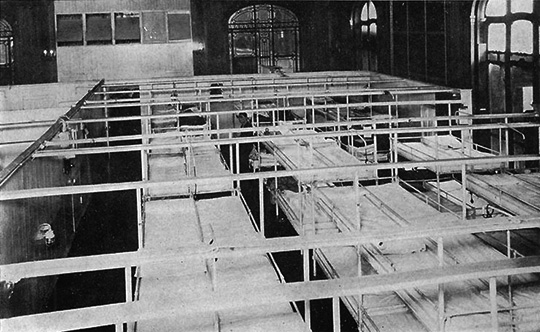

| Leviathan Sick Bay, 1919 Halftone reproduction of a photograph taken in the ship’s sick bay, circa 1919. Note the elegant doorway and windows, left over from her time as the German passenger liner Vaterland. This image was published in 1919 as one of ten photographs in a Souvenir Folder of views concerning USS Leviathan. Photograph and description courtesy of U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command. Donation of Dr. Mark Kulikowski, 2007. |

|

Late in the evening of this day the E deck ward was opened on the starboard side, and was filled before morning.

The conditions during the night cannot be visualized by anyone who has not actually seen them. Pools of blood, from the severe nasal hemorrhages of many patients, were scattered throughout the compartment, and the attendants were powerless to escape tracking through this mess because of the narrow passages between bunks. Everyone called for water and lemons and oranges. A plentiful supply enabled their desire to be gratified. But within a few minutes of the first distribution of fruit, the skins and pulp were added to the blood and vomitus upon the deck. The decks became wet and slippery; the filth clung to the clothing of the attendants; groans and cries of the terrified sick added to the confusion of the applicants clamoring for treatment, and altogether a true inferno reigned supreme.

As noted above, the sick bay was filled a few hours after leaving Hoboken. Until the fifth day of the voyage few patients could be sent to duty because of great weakness following the drop in temperature as they grew better. The E deck ward was more than full all the time, and there were many ill men in various troop spaces in other parts of the ship.

Morning of the 24 of October brought no relief. Things seemed to grow worse instead of better.

The first death from pneumonia occurred on this day, and the body was promptly embalmed and encased in a navy standard casket.

October 3, 3 deaths; 900 cases.

October 4, 7 deaths. The sea was rough and the ship rolled heavily. Hundreds were miserable from seasickness and others from terror of the strange surroundings and the ravages of the epidemic.

Each succeeding day of the voyage was like those preceding, a nightmare of weariness and anxiety on the part of the nurses, doctors and hospital corps-men. No one thought of bed for himself, and all hands worked day and night. On the 5th there were ten deaths, on the 6th there were 24, and on the 7th, the day of arrival at our destination (Brest), the toll was 31. The army ambulance boat was promptly along side, and debarkation of the sick began about noon. The sick bay was cleared first, and we at once thereafter began to clean up in preparation for the wounded to be carried westbound. E deck was then evacuated, but all the sick could not be handled before night, about 300 remaining on board.

On the 8th these were taken off by the army, but not before 14 more deaths had occurred. The nurses remained until the last sick man was taken off.

It is my opinion that there were fully 2,000 influenza cases on board during the voyage. Pneumonia cases must have numbered at least 100, but in the unavoidable confusion due to the rapid spread of the influenza it is impossible to be exact.

Cases of pneumonia were found dying in various parts of the ship, and many died in the E deck ward a few minutes after admission. Owing to the public character of that ward, men passing would see a vacant bunk and lie down in it without applying for a medical officer at all. Records were impossible, and even identification of patients was extremely difficult because hundreds of men had blank tags tied about their necks, many were either delirious or too ill to know their own names; 966 patients were removed by the army hospital authorities in France.

Deaths—Ninety-one deaths occurred among the army personnel, of whom one was an officer, as follows:—

October 2d, 2 deaths

October 3d, 3 deaths

October 4th, 7 deaths

October 5th, 10 deaths

October 6th, 24 deaths

October 7th, 31 deaths

October 8th, 14 deaths

October 10th, 1 death

Crew of Leviathan. 5 deaths

On board ship Col. Fred B. Thomas of Montpelier was commander of the guard; Lieut.-Col. B. S. Hyland of Rutland was in charge of the messing. These officers performed their duties with ability. Among the other officers Capt. Guy Cowen of Rutland and Capt. John F. Sullivan of St. Albans had important positions and rendered most efficient service. The administration force of the regiment was crippled.

All the sergeant majors with the exception of Frank McLaren of Bennington were sick. McLaren was on duty day and night, and he did his work with a cheerfulness that was heartening to all who came in contact with him. Capt. C.N. Barber of Northfield, regimental adjutant just recovering from an operation, laboring under great suffering, stuck to his post as long as possible.

|

|

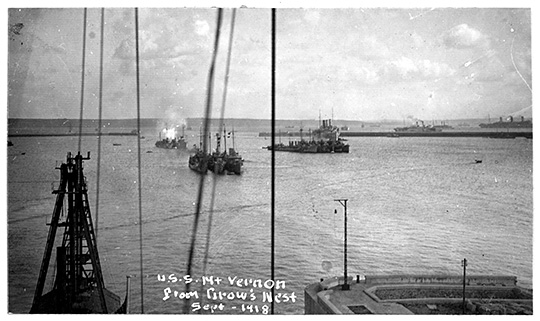

| Harbor in Brest,

September 1918 Harbor in Brest, France, as seen from the Crow’s Nest of USS Mt. Vernon. USS Leviathan [is visible] in outer harbor. Photograph and description courtesy of U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command. |

|

Upon the arrival at Brest the organizations were lightered ashore and were marched about five miles to the mud flats beyond the city of Brest. This proved a repetition of our march to Alpine Landing. The lassitude of the men made it impossible for hundreds of them to make camp with their comrades. They were picked up by Y. M. C. A. and K. C. men and ambulances and taken, to hospitals or helped into the camp. That night the men slept in their pup tents and in the mud.

The only entrance to the camping area was through a lane filled with slippery French mud. The two adjutants were up good a portion of the night lighting the stragglers down the lane to where their companies were billeted. Several hundred never reached camp or their organizations. The hospital record shows that 123 of our regiment died at the Kehruon hospital, nearly 40 at Base Hospital No. 33, several at the Naval Base Hospital and some at Landernau. All of these deaths occurred within a few days of landing. The remainder of the regiment almost immediately proceeded to the advanced sector, and several more men died at Base Hospital No. 15 at Chaumont, and the hospital near Humes.

|

|

| Close-up view, unloading ambulances at Receiving Ward. U.S. Army. Base Hospital No.15, Chaumont, France. The National Library of Medicine believes this item to be in the public domain. |

|

In those few tragic days Vermont lost some of her finest young men. The names of some of the Vermonters follow:—Lieut. William P. Tighe, Rutland; Reg. Sgt. Major Elmer A. Gray, Brattleboro; Color Sgt. Thomas A. LaFond, Rutland; Sup. Sgt. Charles M. Beckwith, Bethel; 1st. Sgt. E.H. Johnson, Lyndonville; 1st. Sgt. R.D. Wakefield, Burlington; Sgt. Gordon A. Preston, Fair Haven; Mess Sgt. Fred F. Bastian, Brattleboro; Sgt. Joseph Yarker, Brattleboro; Cook Eugene J. Belanger, Montpelier; Corpl. Howard L. Bailey, Johnson; Corpl. Francis A. Guild, Orleans; Priv. John A. MacDonald, Brattleboro; Corpl. Grover, Townshend; Corpl. Arthur J. Desilets, Montpelier; Priv. Walter E. Webb; Priv. Carmi Reed.

Nearly 200 of our regiment, men who died at Brest, are buried in the American cemetery at Lambezellec.![]()

At the war’s end bodies from temporary cemetery at Lambezellec were either shipped home for reinternment if families so desired or reinterred at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in northern France.