print preview

print previewback SUSAN GLASSER

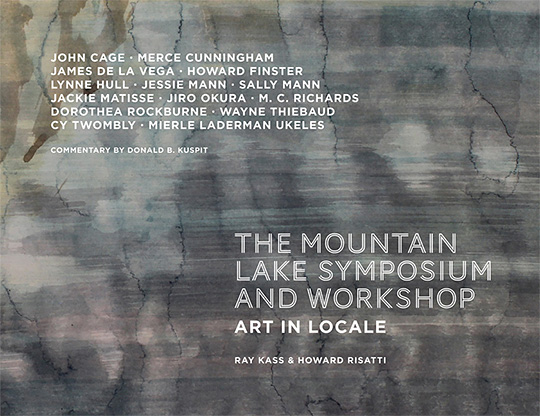

The Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop: Art in Locale

In 1987, Dirty Dancing was filmed at Mountain Lake Lodge in Pembroke, Virginia (population 1,128).1 Befitting a movie about a “sleepy resort,” the real lodge even today promotes itself as “the ideal destination for those seeking the serenity only the mountains can provide.”2 Rurally located near the border of West Virginia, it may be enticing for a weekend getaway but an unlikely venue for prescient discussions about contemporary art. Yet beginning 1980—seven years before Jennifer Grey and Patrick Swayze danced through the Lodge—it became exactly that. With the publication of a catalogue that exhaustively documents the experiment, The Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop: Art in Locale, by Ray Kass and Howard Risatti, it’s worth assessing if the project resonates in 2020, a decade after the last programs concluded.

|

The Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop, launched in 1980, was originally organized as a fall symposium at the Lodge followed in the spring by a related workshop at nearby Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (more commonly known as Virginia Tech). This format, with some additions, continued until 1990. From then until 2009, the yearly programs generally omitted the symposia and added assorted exhibitions, performances, and travel excursions. Thanks to the efforts of Virginia Tech, in partnership with key collaborators at Virginia Commonwealth University, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Mountain Lake Lodge found itself host to the likes of Stephen Addiss, John Cage, Anthony Caro, Howard Finster, Suzi Gablik, Clement Greenberg, Allan Kaprow, Joseph Kosuth, Rosalind Krauss, Donald Kuspit, Kay Larson, Sally Mann, Charles Miller, Ed Paschke, Robert Pincus-Witten, Tim Rollins, Kay Rosen, Irving Sandler, Nancy Spero, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Wayne Theibaud, John Yau, to mention a few!

~

In its nascent years, the organizers aspired to examine art’s “shared values that are not purely economic.”3 Given its inception during the bacchanal decade that birthed the likes of Julian Schnabel, Jeff Koons, and Eric Fischl, that emphasis already portends the project’s inclination to swim against contemporaneous currents.

The 1980s art scene was predominately market driven and from the 1990s onward, contemporary social issues and agitprop have been driving forces.4 Even now, much of the art world is mired in the commercial and sociopolitical zeitgeist of the day. The art in the 2019 Whitney Biennial was also filled with politically loaded topics like anti-Trumpisms, climate change, and race and gender identity. So pervasive were these newsy contemporary topics that the critic Holland Cotter noted the rarity of artists with substantive things to convey:

“For a handful of artists, to reclaim history is to reassert the power of spirituality. And the acknowledgment of this element, generally shunned by the market-centered contemporary art world, may be the exhibition’s one truly radical move. In a sculpture titled ‘Maria-Maria,’ the Afro-Puerto Rican artist Daniel Lind-Ramos creates, from wood, beads, coconuts and a blue FEMA tarp, a figure that is both the Virgin Mary and personification of the hurricane that devastated the island in 2017. Enshrined in a sixth floor Whitney window, the piece looks presidingly majestic.”5

At the 2019 Venice Biennial, of-the-moment jeremiads included housing, racism, human migration crisis, borders, gender, war/violence, South African education, inequality, climate change, political anger, civil rights, and crisis trauma. A singular reprieve from these polemics, per the art critic Andrew Russeth, was the work of Joan Jonas, whose work “seemed to be searching for a way to make art fulfill a recuperative function.”6 That is to say, art dealing with universal ideas and the larger human condition are scarce in today’s art scene.

Participants at Mountain Lake, contrariwise, were attempting to locate “art meaningfully within a larger cultural and social complex,” not as social or political commentary but as a way of exploring the world more broadly.7 To take but one example, the climate crisis is unarguably an important issue and one that serves as creative fodder for artists. But at Mountain Lake, nature and natural forces were investigated from a more philosophical perspective. Artists as diverse as John Cage, Ray Kass, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles were interested in partnering with and learning from nature rather than trying to control it, harness it, or pontificate about it. Their works replaced political tirades with a desire to understand nature’s processes: Cage harnessed the conceptual role of chance in nature,8 Kass’s muse was vorticella (single-celled forms) that “symbolize nature at a level deeper than simple visual representation,”9 and Ukeles was inspired by the life-sustaining processes of invisible anaerobes (organisms that live without oxygen) and used the topic as a metaphor for earth’s many invisible systems.10 None of these artists used nature as its own subject matter or to advocate a political agenda; rather, their interest was trying to understand the workings of the natural world and one’s relationship to it.

~

The earnestness of the Mountain Lake project throws into high relief the superficiality of much of today’s bombastic art; art is not going to solve the climate crisis (as an example) or even promote an awareness of issues in any way that isn’t better achieved by political action, news articles, and documentaries. But it can remind us of why we should care, why nature defines us as much as we shape it.

Originating out of the School of the Arts at Virginia Tech, one might expect the Mountain Lake project to have hewn closely to a standard art discipline typical of most college art departments in the 1980s. It is curious then, that the project had a penchant for interdisciplinarity as distinct from a single discipline or multidisciplinary approach.

Multidisciplinarity is a methodology that juxtaposes disciplines to foster wide knowledge while maintaining the rigor of individual disciplinary practices. Multidisciplinary projects use parallel relationships between different disciplines whereby partners work alongside each other without working in an integrative way.11

Throughout the twentieth century the academy was structured by disciplines that each developed their own methodologies, values, knowledge, and worldviews. When experts from different fields collaborate in multidisciplinary projects, they still generally maintain their own discipline-dictated conventions.

In the twenty-first century the collaborative trend is toward discipline-dissolving interdisciplinarity. Interdisciplinarity integrates and blends the theories, content, and methods of different disciplines to investigate the world in ways that cannot be adequately pursued by any single specialty.12

Some have argued that the former approach emphasizes knowledge, the latter strives for understanding.

“Knowledge consists of helpful information: all the learned facts, rules, definitions, formulae, etc. that we can recall and use appropriately. Understandings are different. They are not facts but ideas about facts.”13

From this perspective, it makes sense that the Mountain Lake project privileged interdisciplinarity. It is an approach in keeping with its motivating conviction that art is a useful tool for making sense of the world beyond art.

Over the years, the project integrated—in shifting combinations—such disparate disciplines as art history and art making, philosophy, music, architecture, sociology, psychology, religious studies (Eastern and Western), urban design, theater, ancient crafts, and environmental science.

As Jessie Mann, a contributing artist who participated in one of the later year workshops, stated:

“ . . . in the same way that some of the most important scientific discoveries come from collaborations across disciplines, so too for art. It can take a lifetime of steady work to master one medium or area of study, and to bring together diverse practitioners, each with years of practice and focus, creates a synergy the result of which is much greater than the sum of the parts that compose it. The national scientific grant structure is increasingly favoring trans-disciplinary proposals, and the Mountain Lake Workshop is the artistic equivalent of this effort, but one which has been in existence, well ahead of the intellectual curve, for decades. . . . It was a great honor to be involved in such an extraordinary and prescient structure . . . ”14

The most extensive interdisciplinary project undertaken as part of Mountain Lake was Ki No Ichiku (“Relocating the Tree”), which transpired over three years and two continents.15 Japanese and American students and a wide swath of experts in the fields of art, architecture, landscape architecture, industrial design, interior design, history, English, philosophy, engineering, and physics participated. Three projects meant to “relocate the tree,” or knowledge imparted to participants demonstrate the power of an interdisciplinary approach: a Moon Viewing Pavilion,16 a Rammed-Earth Wall,17 and the Nisso Screen.18 The shared hands, minds, and disciplines required to make these architectonic structures produced amazing art. But equally important, the communal experience of their creation put the how of the projects on par with the what of the projects. The communal makers gained life lessons that may inform each participant’s understanding of their creative relationship to others and to the larger natural world. Collective creativity can be impressively successful because it exceeds the capabilities of any one expert or discipline.

~

The art of our time has generally been an ego-rich discipline. This was particularly pronounced in the art world during the early years of the Mountain Lake project, when the craze for artist superstars like David Salle, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat predominated. From its inception, the Mountain Lake project ignored this trend choosing instead to explore the creative energy of collaboration. This concept complements interdisciplinarity: discipline specificity tends to champion individual experts while interdisciplinarity requires a more egoless approach.

A hallmark of the workshops was a collaborative art making effort meant to create meaningful experiences for all participants.19 Even though many of the workshops were led by artists and critics of national note (John Cage, Howard Finster, Donald Kuspit, Suzi Gablick, et al.), resulting works were collectively produced by “anonymous” participants.20 Even nature was introduced as a collaborative partner.21

Collaboration—moving “beyond the scope and expertise of any single individual”22—was also often paired with the use of chance as a means of suppressing participants’ egos. Since the experiments of the Surrealists, chance has proved a means to waylay intention, relinquish control and squelch self-expression. Chance opens one up to new ways of seeing and understanding. It can also challenge one’s habits of thought “so that new concepts can develop that expand our understanding of ourselves as well as the world around us.”23

And finally, the emphasis on non-egocentric processes complemented the project’s exploration of a larger context for art. One of the “motivational features” of the project—from its symposia, workshops, and exhibitions—was creating a community that could construct its own “critical dialogue about contemporary issues.”24 The result was that each progressive symposia and workshop built on what came before and created a culture of shared values and meanings that allowed participants to eschew contemporaneous art trends. Instead, they strove to use the discussions and making of art to explore issues that matter to the world beyond art.

The catalogue’s concluding paragraph summarizes it best:

“Through their emphasis on collaboration and chance, the Mountain Lake programs have attempted to open and explore a pathway to give the individual and collective imagination the potential to realize a meaningful and socially responsible relationship to the world around it through the aesthetic experience. It is in this way that the programs of the Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop attempt to situate art within a larger realm of culture, a realm of culture that is cognizant of the social context in which art must exist in order for it to provide a meaningful experience for both makers and viewers.”25

Collaboration and chance serve the same function in the project workshops as interdisciplinarity by encouraging participants to move past ideological certitude whether discipline or ego-based. Suppressing one’s ego, inviting a collaborative process, and embracing chance can also produce exquisitely arresting art. Cage’s relinquishing of decision-making by using the I Ching in the selection of and placement of rocks for the series, “New River Watercolors”26; the Japanese artist Jiro Okura’s collaboration with forty-two Japanese and American students taking turns executing Zen-like calligraphy lines to make the Nisso Screen27; and Howard Finster inviting community members to use his “demention” stencils to paint their own portraits—because anyone who “holds the brush” contributes to the spiritual messages he sends out into the world.28

~

Though set very specifically in rural Virginia, the Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop project twisted the notion of regionalism into something (ironically) provincial in two ways.

First, it rejected the pejorative twentieth century concept of regionalism as connoting local interests, idiosyncratic styles, and unsophisticated sensibilities. In the peripatetic world of the twenty-first century, this notion is both fallacious and unhelpful. From the beginning, the originators of the Mountain Lake project had a conviction that art is more than what happens in art centers like New York City.29 They understood that smart ideas are not geographically dependent; aesthetic IQ cannot be pinpointed on any map.

Despite its secluded location at the Mountain Lake Lodge, the founders aspired to bring informed people from diverse disciplines together for colloquies aimed at defining art’s contributions to “understand[ing] the wide world better.”30 For a span of nearly four decades, artists, musicians, critics, historians, Zen experts, architects, evangelical preachers, gallery directors, filmmakers, curators, et al., congregated in a single small locale to cogitate on Big Ideas. The locale for this project was important only insofar as it existed in a defined place that supported community and collaboration—but it could have been any place—a concept alien to the regionalism of artists like Grant Wood and Thomas Hart Benton.

Secondly, the project recognized and constructed a solution to a problem that has failed to gain much traction in cultural discourse: the loss of shared stories and values. In an art world that is predominantly liberal and has a penchant for political posturing, it may be misconstrued that there are, in fact, shared values represented in today’s art. But this erroneously conflates political agendas with larger cultural beliefs, and moral and social values. The Mountain Lake project’s “regionalism” was actually an organizing device to encourage participants—many of whom participated from year to year—to reestablish a set of collectively shared values and ideas.

For much of Western art history, this was not a pronounced challenge for artists. Over the centuries there existed communal tropes upon which much of art was based: biblical stories, classic mythology, and widely circulated cultural symbols, among others. These provided a kind of short-hand that artists relied on to convey ideas about shared human experiences and the human condition more broadly. By the twentieth century much of that commonly possessed vocabulary was no longer pervasive (its closest relative today being pop culture; e.g., the opening paragraph of this essay).

What made the Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop project so valuable was a near perfect complement of convening a mélange of thoughtful people immersed in big ideas, a commitment to an interdisciplinarity that did not privilege one body of knowledge over another, a conviction in the potential of collective creativity, and a longitudinal effort that shaped a shared set of values, ideas, and meanings.

For all these reasons, the ideas and issues explored in the symposia, workshops, and exhibitions at Mountain Lake remain germane to the cultural discourse in 2020: defining a role for art in a larger world context, employing interdisciplinary to its investigations, privileging community in the creative process, and redressing provincial notions of regionalism. And if all of that were not enough to recommend dipping into The Mountain Lake Symposium and Workshop: Art in Locale catalogue, it is also worth taking a look at much of the art produced during the project’s four-decade run. The best of it was unafraid to traverse the realm of ideas and of the spirit, and celebrate the sublime in the mundane in ways infrequently seen in art today. Replacing timely topics with timeless themes is a need as pressing today as it was during the life of the Mountain Lake project. ![]()