print preview

print previewback BLACKBIRD EDITORS

Recommendations & Reviews

This spring, the Blackbird Editors present reviews and recommendations of books that have

been particularly enticing lately, from Ocean Vuong’s highly acclaimed On Earth We’re Briefly

Gorgeous, to John James’ debut poetry collection The Milk Hours, to Claire Wahmanholm’s

remarkable second collection Redmouth.

The Milk Hours, by John James | Review by Danielle Kotrla

Milkweed Editions, 2019

|

Countless philosophers and theorists have mused about language’s ability (or not) to capture experience. For instance, Ludwig Wittgenstein famously wrote in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” However, John James’ debut collection of poems, The Milk Hours, challenges this assumption as to what one should or should not speak by making his approach to capturing experience particularly clear. “If approximations are the best / We can do—fine then,” he writes in one poem, “let’s approximate.” And though they may be mere approximations, the poems in this collection come as close as is seemingly possible to capturing the in between, those hours between birth and death that we call a life.

The poems work together to acknowledge an interesting dynamic—despite their precision and dedication to approximating as exactly as possible, the poems also seem to question the importance of actually getting the terms right. For instance, the collection’s title poem reads, “Cattail, heartseed—these words mean nothing to me.” As the speaker mourns the death of his father and visits his grave, his sense of loss of both the father and the actual value of words presents the key to the aforementioned paradox. In the same poem the speaker later writes, “From our porch I watch snow fall on bare firs. Why does it / matter now—what gun, what type.” Despite the immediacy of the poem’s landscape, the speaker seems to be calling into question the importance of these details and what they mean when placed into a world that continues to take.

The meditations on grief that comprise this collection circle these and other unresolvable questions, but even without finding answers the speaker seems to tease out some possibility of hope. In “Poem for the Nation, 2016,” the speaker shares a tender moment with his partner as they sit together on the Capitol lawn with their young daughter. The poem ends with the observation that “All we ever needed / was a start.” And though a sense of foreboding colors the time and place of this particular poem, there is still the daughter eating a halved grape, mallards spinning on the Potomac. There is still the lover’s hand, pressed to the speaker’s lips. Ultimately, despite the brief, singular moments described in each of these poems, this striking debut collection seem to be acknowledging the landscape’s potential to hold both loss and new life; how our daily lives are filled with not only grief and absence but also small, yet critical, moments of joy and promise.

John James is the author of The Milk Hours (Milkweed Editions, 2019), selected by Henri Cole for the Max Ritvo Poetry Prize, and the chapbook Chthonic (Cutbank, 2014). His work has been supported by the Bread Loaf Environmental Writers’ Conference, among other awards and fellowships.

~

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, by Ocean Vuong | Review by Rebecca Poynor

Penguin Press, 2019

|

Ocean Vuong’s debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, envelops the reader in a nonlinear, fractured narrative told through letters from the narrator—identified only as Little Dog, a nickname with which he has a complicated relationship—to his illiterate mother. Though fiction, the individualized nature of these letters, each telling its own moment, invoke the feeling of reading a collection of rich prose poems. These letters are connected by the unfolding storyline of Little Dog growing up in Hartford, Connecticut in the 1990s, raised by his abusive but loving mother, Rose, and his schizophrenic grandmother, Lan, as he struggles with language, identity, intergenerational trauma, and, eventually, love. Little Dog tells not only his own story, but Rose and Lan’s as well, drawing the novel through Little Dog’s present and his family’s past in Vietnam in emotionally charged, often grisly, but consistently exquisite scenes that detail the trauma faced by the family.

Vuong writes, “A name, thin as air, can also be a shield.” Though Little Dog points out the negative connotations of the name Little Dog, a nickname bestowed upon him by Lan, he uses it as a shield by self-identifying with it throughout the entirety of the novel, never letting the reader know him beyond this marker. Little Dog often and abruptly addresses the “you” of the novel, reminding the reader who the addressee really is, and who Little Dog is protecting himself from—his mother. Though, as both the reader and Little Dog are devastatingly aware of, Rose may never get the opportunity to read the letters herself, her illiteracy and the language barrier between mother and son a constant.

What drew me to this notable novel is its evocative lyricism, a reminder that Vuong’s home genre is poetry. It is the surprising but striking language that sustains this novel and is reinforced by Little Dog’s own insistence that, despite their trauma, he, his family, and their story are beautiful.

Ocean Vuong is the author of the bestselling novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press, 2019), and the critically acclaimed poetry collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press, 2016). A recipient of many awards and honors, including the 2019 MacArthur “Genius” Grant, he currently lives in Northampton, Massachusetts where he teaches in the MFA program at UMass-Amherst.

~

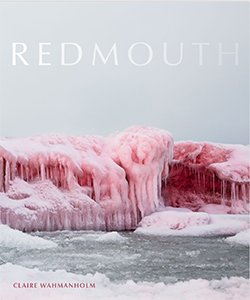

Redmouth, by Claire Wahmanholm | Review by Hayley Graffunder

Tinderbox Editions, 2019

|

Immersed in a natural world fast-tracked for ruin and the grief-stricken dreamscape that emerges as a result, Claire Wahmanholm’s second collection explores the indissoluble grief of environmental devastation and through it, if unsullied hope is not possible, then strength—maybe even adaptability. Wahmanholm tests the physicality of language and voice, stalks humanity’s journey as both predator and prey, and closes the door to optimism—but cracks a window to give transformation a chance.

Early in the book, the poem “Preserves,” lays groundwork for sound to take a carnal shape and in doing so, examine the limits of language. In a devastated forest, animal calls, like their homes turned to lumber, “lie in stacks along the path: / songbird bindle, parcel of fox throats, / packet of bobcat hollers.” This synesthetic visual image of sound and its absence prompts the speaker to mourn her own voice, and thus her power: “My own calls / are hollow and numb in my neck, / and what would come to that kind of call?” The poem returns the speaker to her place as an individual animal, asking the reader to grieve not only for life cut down, but for the voice that is swallowed when a collection of humans becomes its own predator.

Becoming at once predator and prey is only one example of the complexity and paradox coexisting within the astonishing lyric mode of this collection. Even while teasing out the limits of language, Wahmanholm’s poems are rife with linguistic and lyric invention. Like the erasure poems that create anew while letting us see faintly the lyric from which they were born, so too does Wahmanholm allow us to understand the ravaged earth by showing, softly, what it used to be, what power it still holds. In “The Snow Reckoner,” the speaker understands that power—knows “this field is a body that could swallow me whole.” The human is not god but an animal, the earth an animal too, with a mouth that insists “a body and a field are one horizon.”

A collection of such deft innovation, of complication that only leads closer to the truth, Redmouth offers poems that spark revelations each time they are read. In “Given,” Wahmanholm encounters Euclid’s idea that “a point is that which has no part,” thus pulling the reader into an exercise in extricating the inextricable: “no matter / how fast / it flies, / a bluebird’s / blue can / never outstrip / its bird, or butter / drain from / its cup.” How then, could we take red from mouth, grief from stricken? ![]()

Claire Wahmanholm is the author of Redmouth (Tinderbox Editions, 2019), Wilder (Milkweed Editions, 2018), and the chapbook Night Vision (New Michigan Press, 2017). Her third collection, Meltwater, is forthcoming from Milkweed Editions in 2023. A 2020–2021 McKnight Writing Fellow, she lives and teaches in the Twin Cities.