|

DAN O’BRIEN

The Dear Boy

3a.

(In darkness, climbing stairs, giddy and out of breath:)

ELISE

I can’t believe what you did—!

FLANAGAN

I know but it felt so good—!

|

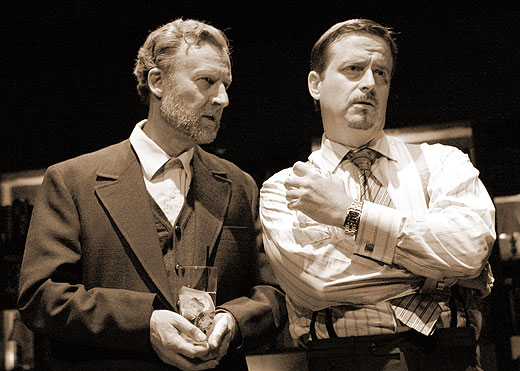

Daniel Gerroll as Flanagan, T. Scott Cunningham as Richard

|

Photo by Richard Termine

|

ELISE

—Did you see his face?

FLANAGAN

I’ve never seen him at a loss for words; I didn’t think it possible—

ELISE

Everything stopped! Everyone just shut up!

FLANAGAN

We really should keep these guns in the classroom, don’t you think?

ELISE

—Is it loaded?

FLANAGAN

You know, I haven’t even / checked—

ELISE

—Don’t look now!

(He cries out:)

FLANAGAN

— !

ELISE

Are you all right . . . ?

(She reaches out, with her hand, to steady him in the dark . . . )

FLANAGAN

I’m fine; I fell—I almost fell . . .

(If we could see, we’d see him pull away from her.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

. . . Is it always so dark inside your building?

ELISE

(the sound of keys; she’s disappointed)

It’s not my building . . .

(She opens the door; light grows:)

3b.

(Books everywhere, as if the walls are made of books.

A kitchen table, two chairs.

FLANAGAN heads straight for the books in the downstage “wall,” head held horizontal to read the titles off the spines.)

ELISE

The people that live here are writers.

FLANAGAN

Are they? Where do they teach.

ELISE

They don’t; they’re poets. —They’re both poets, believe it or not . . .

FLANAGAN

How romantic . . .

(She spills her keys across the tabletop.)

ELISE

. . . Do you want a drink?

FLANAGAN (looks up)

. . . ?

ELISE

Sorry. I forgot.

FLANAGAN

—No actually I would.

I tell people I’m an alcoholic, you see, because it seems to put their minds at ease. —They expect it of me, somehow . . . —While the truth is I simply prefer not to.

(He tries to laugh.)

Except on very special occasions.

ELISE

Is this a very special occasion . . . ?

FLANAGAN (trying for suave)

We shall see. —Won’t we.

(She smiles—a little—moves to a cabinet or shelf.)

ELISE

Wine?, or Scotch?

FLANAGAN

Please.

ELISE

Which; both?

FLANAGAN

A glass of wine would be fine . . .

—A bottle of wine would be divine . . . !

ELISE

. . . I don’t think I have a full bottle . . .

FLANAGAN

I’m just being—humorous—.

Let me see here . . .

(He studies the titles of the books.

She uncorks an already opened bottle of cheap Merlot, pours it into two shallow glasses.)

ELISE

(bringing his glass to him)

. . . I don’t have any clean wine glasses . . .

(He takes it. She watches him awhile.)

ELISE (cont’d.)

(as if disappointed)

. . . You weren’t going to kill him, were you . . .

FLANAGAN

Whom?

ELISE

Richard. He deserves it, you know . . .

FLANAGAN

No; of course / I wasn’t—

ELISE

You pulled a gun on him.

FLANAGAN

I wanted to frighten him, that’s all—to shut him up.

ELISE

Why?

FLANAGAN (the books, again)

. . .

ELISE

(flirtatiously)

You’re going to get in trouble . . . You’ve done a very bad thing, Mr. Flanagan . . .

(She smiles.)

You can not pull a gun in public and then just walk away. There’ll be hell to pay come Monday.

FLANAGAN

Monday’s Christmas Eve.

ELISE

You could be arrested.

FLANAGAN

—Let them do their worst / to me!

ELISE

They might look for you here, you know . . .

FLANAGAN (trying for playful)

Will they? Tonight?

ELISE

Maybe.

FLANAGAN

Do they know where we are?

ELISE

It’s not hard to figure out.

FLANAGAN

—Do they know where you live?

ELISE

That’s not hard to figure out either . . .

(He contemplates his drink.)

FLANAGAN

Then we must hurry up, Ms. Sanger. Mustn’t we.

ELISE (smiling)

Hurry up with what exactly, James . . . ?

FLANAGAN

. . .

(He returns his attention to the books.

She watches him some more.)

ELISE

. . . See anything you like?

FLANAGAN

. . . ?

ELISE

Books.

FLANAGAN

—No: I’m afraid I’m not a fan of most modern literature. Word-salad.

ELISE (entertained, perhaps)

Word what . . . ?

FLANAGAN

That’s what it’s like for me: art for art’s sake—like a salad, made of words.

ELISE

As opposed to . . . ?

FLANAGAN

—How do you mean?

ELISE

Art for what’s sake then—?

FLANAGAN

—O, for God’s sake, I suppose.

(Smiles tightly.)

For the sake of humanity . . .

(He raises his glass:)

Sláinte!

(Pronounced “Slan-cha.”)

ELISE

Excuse me?

FLANAGAN

Irish. Gaelic. —“Cheers”—bottoms up!

(She raises her glass, too.)

ELISE

(approximating)

Sláinte!

FLANAGAN

Indeed . . .

(They drink. He clears his throat.

He returns to the books; so she sits down . . .

She kicks off her heels, places a bare foot up on the corner of the table . . .

He notices.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

. . . It’s remarkable, really, to see so many books inside one room . . .

ELISE

They’re everywhere. Every wall-space is covered: the bathroom, bedroom—I’ll show you—

FLANAGAN

—No, thank you.

(He glances at her foot again.)

—But thank you. This is fine for me now . . .

(The books again; he sips furtively at his wine.)

ELISE

. . . They had them instead of children . . .

FLANAGAN

O yes I can see that—

ELISE

Instead of braces or bicycles or college: they bought books.

I like that, I think . . .

I don’t know if either one of them had a problem with fertility or what—

FLANAGAN

You speak of them as if they’re dead.

(He looks up at her.)

ELISE

Well it feels that way, doesn’t it?

When I moved in here, at the end of summer, I had this feeling like they were here, always—with me . . . You know? . . . Like ghosts.

FLANAGAN (mild alarm)

Ghosts?

ELISE

Don’t worry: they’re in Paris. As far as anyone knows . . .

I mean, isn’t that perfect . . . ?

They send me these postcards once in a while. They’re friends of my parents . . .

—But: it was like I had broken into their apartment, you know?, while they were gone, and I was pretending to be them; both of them . . .

. . . It was a very confusing time for me last summer.

FLANAGAN

I imagine it was / that . . .

ELISE

I kept having this one recurring dream, a nightmare, where they’d come home unannounced.

FLANAGAN

You’re paying rent here, aren’t you?

ELISE

. . . ?

FLANAGAN

—You’re paying rent on this place?

ELISE

Of course I’m paying / rent—

FLANAGAN

Then you have nothing to be ashamed of, my girl.

ELISE (short)

—Who was saying anything about shame?

FLANAGAN

. . . I’m sorry . . . I misunderstood . . .

ELISE (she’s playing with her keys)

. . .

FLANAGAN (head bends to books again)

. . .

(She gets up: pours herself more wine.)

ELISE (a challenge)

I thought you said you were fifty-nine.

FLANAGAN (head up)

Did I?

ELISE

Before: Richard—he said / you’re—

FLANAGAN

—O. You see, I lied about that too . . .

ELISE

. . . Why?

FLANAGAN (shrugs)

Vanity, I suppose . . .

ELISE

You don’t strike me as very vain, Mr. Flanagan . . .

FLANAGAN

You’d be surprised, Elise.

(Smiles: teeth.)

—And I don’t feel sixty-five.

ELISE

You don’t act sixty-five . . .

FLANAGAN

Don’t I . . . ?

ELISE

(“No,”) you’re not old enough to retire, I don’t think . . .

FLANAGAN

Amn’t I?

ELISE (smiles; perhaps charmed)

—What is that?

FLANAGAN

What.

ELISE

That word: “Amn’t”—?

FLANAGAN

“Amn’t,” yes—

ELISE

Is that really a word?

FLANAGAN

It’s a contraction, actually—

ELISE (sitting again)

—Are you English?, or Irish? —I never could figure that one out . . .

FLANAGAN

I’m neither. —I’m American.

ELISE

All right: but where are you from?

FLANAGAN

The Bronx.

ELISE

As in Bronx, New York . . . ?

FLANAGAN

I live in Manhattan now . . . But I grew up in the Bronx. —I was Irish, from Ireland, as a boy.

ELISE

And you never outgrew the accent?

FLANAGAN

I should hope not!

ELISE

. . . It’s almost more English than Irish . . . More an English-public-school-kind-of—Eton, or—“Harrow,” is it . . . ?

FLANAGAN

Pretentious, you mean.

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN

You think I speak in a less than truthful manner?

ELISE

I don’t know if it has anything to do with being “truthful,” James . . .

FLANAGAN (back to the books)

. . .

ELISE

. . . Are you married?

FLANAGAN

No, no, no . . .

ELISE

—The students think you are.

FLANAGAN

That’s because I tell them I am so.

ELISE

Why do you lie to them?

FLANAGAN (straightening up)

It’s a performance, isn’t it? You’re playing a part. Most teachers are villains, or they are clowns: both are the teachers without talent; their appeal is wholly low-brow.

But those of us who are burdened with more—sophisticated tastes: we create subtler personas, full of shadow and light, mystery, and more often than not a wife.

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN

No one really trusts a male teacher anyhow, Ms. Sanger. Much less a bachelor.

ELISE

Why do you think that is?

FLANAGAN

You’re very curious about me tonight, aren’t you?

(She smiles, as if shyly. He drinks the rest of his wine, sets it down upon her table.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

. . . And you?

(With great courage, effort:)

Are you—seeing someone . . . at the present time?

ELISE (a long exhalation)

. . . I was . . . For a long time: six years. —Not married though, thank God . . .

We broke up. —It was mutual. —We outgrew each other. —We changed. I love him dearly, but—will you listen to me?

FLANAGAN

. . . ?

ELISE

—I’m so fucking full of clichés! It’s like a fucking first language—I know absolutely nothing about life . . . !

FLANAGAN

I think you know a great deal. That’s why I hired you.

ELISE

—I’m not talking about literature, James . . .

FLANAGAN

. . . Would you like some more wine?

(He takes her glass; careful not to touch her hand.

She watches him as he pours.)

ELISE

. . . How do you do it?

FLANAGAN

How do I do what . . . ?

ELISE

You teach: and you love it. And when you don’t love it you at least feel

proud. You’ve got a martyr’s pride . . .

Because I’ll tell you something: I’m good at it. Teaching. The kids love me—and I can’t stand them. —I hate them—the kids—I hate “kids” . . . And the children at that school can all eat shit for all I care: I mean, this attitude they have—? They look down on you as a matter of course, as if it’s somehow polite of them to condescend to talk to you, because you don’t live there—you can’t afford to! —So I constantly feel this need to shock them, you know? To break them of their smug little complacencies—about life. I flirt with the boys; I wear low-cut blouses, leather minis. I’m a bitch to the girls; I confront them with symbolic gang-rape in Lord of the Flies—and they are shocked! —Thank God something shocks them!, for a moment, for a few days, they’re confused, and violated . . . Why would she do this to us? What’s Miss Sanger trying to say . . . ?

But they get used to it, don’t they . . .

They’ve started to laugh at me already: “O, that’s Miss Sanger”—they don’t use the word Ms., it’s like their mouths are congenitally incapable of forming the sounds required—“That’s our Miss Sanger for you: it’s because she’s so young . . . ”

Don’t get me wrong: it’s me: I’m an artist—a novelist; by nature. That’s what I wanted to be in the first place, when I got out—of college. I went to Brown? I wrote a novel as my senior thesis. It’s not that good: too long—it’s trite—Richard read it; he had lots of notes . . . It’s not organic just yet, let’s just put it that way; but it’s a start . . . It’s about a place, in case you’re wondering, very much like Brown: there’s a murder, yadda yadda yadda . . . I haven’t given up on it just yet.

. . . But once you grow up, and by “up” I mean twenty-six,

-seven, you find you’ve got to pay your rent, right? You’ve got to get health insurance. You have got to get a life, so—wake up! You know? Get married!, have kids quick before your ovaries dry up like a, like what? . . . fruit is so—fuck! . . . Anyway: and then you’ve got to find time to be inspired and isn’t that just about the most depressing thing you’ve ever heard . . . ?

FLANAGAN

You’re not a teacher.

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN

That’s simply not who you are.

ELISE

That’s the nicest thing anyone’s said to me in a very long time . . .

FLANAGAN

. . .

(She smiles up at him as she drinks deeply of her wine . . . He moves himself to the bookcase again.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

—Once. —For a long time when I was young I had that certain ambition of which you speak. I gave myself one year—I was younger than you; and after months and months of sitting at my desk in a state of complete and utter constipation—artistic constipation—I suddenly realized: I had no talent. For looking at myself. I find it boring.

ELISE

And frightening.

FLANAGAN

—No: boring. —Indulgent; I’m not unique.

ELISE

You are. Everyone’s unique if you’re patient enough.

FLANAGAN

You say that because you’re young.

One of life’s great tragedies, Ms. Sanger, is to grow old and realize that while everyone is indeed an individual, no one is unique.

ELISE

I don’t know if I believe that . . .

FLANAGAN (he shrugs)

You don’t have to: it’s true.

You’ll see . . .

ELISE

What did you write about when you were young?

FLANAGAN

Nothing worth reading, I can assure you—

ELISE

Tell me:

FLANAGAN

I wanted to be the next James Joyce. Or Will Faulkner. —No, Joyce: the Irish-American Joyce of Scarsdale! . . . That was my privatemost ambition . . . When I first came here to teach—I was twenty-three years old—I was obsessed with that place; this town: Scarsdale . . . There were not so many Jews then. —It was Episcopal: a blue-blood town. This was ’49 into ’50—Joyce was still quite shocking then—and I wanted to write a novel like Ulysses, but instead of Leo Bloom one day in Dublin, it would be—well, me: one day in Scarsdale . . . And all our young James Flanagan need do all day was exactly what I did:

Take the seven-fourteen local from Grand Central, empty as it would be in the morning, as it always was, the armies of suburban businessmen in their gray flannel suits, drab trenchcoats and black wool hats waiting up north on their southbound platforms, gazing down along the tracks, into the city . . . —Uptown to Harlem we’d ride, to 125th Street and farther still, up, into the Bronx, and Melrose, Tremont, Fordham, Botanical Gardens . . . The cars fill up with blacks and hispanics—women mostly: nurses, cooks, maids—all the way to Fleetwood, and Bronxville; where the train begins to empty out again: maids and cooks and nurses; the odd merchants and clerks off in the middle-class burgs of Tuckahoe and Crestwood . . . And up farther still till we reached Scarsdale . . . Bright, clear, sun-filled Scarsdale . . . Where I disembark neck-deep in a rabble of hired hands . . . They look at me strangely, almost as if with pity; if I drop something they call out their name for me: Sugar, you dropped yo’ scarf! . . . And across the platform the late men wait for their late train . . . reading the Times, the latest Cheever in The New Yorker, scratching a line or two of original poetry in the margins of their day books . . .

The walk from the station—you know it too: up over East Parkway, down Spencer Place, past the delicatessen where I buy my second cup from the ex-con behind the counter; a packet of cigarettes—I smoked in those days; —and up higher still, up out of the village past the old homes in their crescent-shaped lanes—homes built by the city-rich over a hundred years ago, for the wives and children to escape the immigrants and typhus from the horse dung in the summer in the city . . . There has been a murder in that house: someone killed his wife with a hammer while she slept. In that house there has been a child’s death, by illness or by accident; adultery in that house; bankruptcy, alcoholism, drug-addiction . . . A starvation of affection . . . That house is haunted. That one is empty now. —But that one there is happy. That one is full of children . . .

. . . Up the hill and round the bend at the soccer fields, up over that stagnant brook past those black willow trees, perpetually pruned . . . I climb the stairs to my office in high heartbeat just to write it all down . . .

(With pride:)

Instead I’d prepare my lesson.

(A moment.

He drinks.

He turns to look at the books again.)

FLANAGAN

Tell me of their poetry, Ms. Sanger.

ELISE

My poetry?

FLANAGAN (turning)

—You write poetry?

ELISE

Not anymore. —I thought, when you said—your head was / turned.

FLANAGAN

I meant the poets who live here. —They that haunt you, Elise. What’s their poetry like:

ELISE

I don’t know how to describe it . . . Sort of like a—word salad?

FLANAGAN

Ah.

(Smiles tight.)

ELISE

Yes—

(she smiles too)

and morbid, too. —I don’t like it very much . . .

FLANAGAN

I don’t either . . .

ELISE

—I think you would, actually.

FLANAGAN

—Do you find me morbid, Ms. Sanger?

ELISE

Well, I’d say you’re very serious sometimes, Mr. Flanagan.

FLANAGAN

Yes, but not morbid; not depressive. —I think to have a surfeit of self-pity is a grave, grave sin. —I have great capacity for lightness and mirth.

ELISE (smiles)

“Mirth”?—are you sure . . . ?

FLANAGAN

Yes; you might even say that I am lightsome.

ELISE

I would not say that—I don’t think I even know what that word really means . . .

FLANAGAN

—It means exactly what it says: I have great light inside of me.

ELISE (she’s still smiling)

. . .

FLANAGAN

As do you . . .

(He smiles in return, showing his teeth.

She sips her wine.)

ELISE (a secret)

. . . I found some letters in a box. Would you like to see them?

FLANAGAN

. . .

ELISE

They’re love letters the poets wrote each other years ago, when they were young. —Sexual letters, some of them . . .

(Mock disdain:)

Filthy stuff, really.

FLANAGAN

. . . In what way filthy?

ELISE (shrugs)

The usual . . .

(She smiles:)

And a few not so usual . . .

FLANAGAN

. . .

ELISE

. . . They’re sweet. —And kind of heartbreaking, too. —People do the most disgusting things to each other when they’re in love . . .

FLANAGAN

I wouldn’t know about that.

ELISE

O come on James—

FLANAGAN

I wouldn’t . . . !

I suppose you’d find me rather prudish, if you knew me, when it comes to that sort of thing . . .

ELISE

What sort of thing?

FLANAGAN

—Sex things.

ELISE

There . . . Was that so hard to say, Saint James?

FLANAGAN

. . . What did you call me?

ELISE

. . . ?

FLANAGAN

“Saint James”—?

ELISE

Everyone calls you that: the teachers—. I thought you / knew—

FLANAGAN

No . . .

ELISE

—I was teasing.

FLANAGAN

Were you? Why?

ELISE

Why was I teasing / you . . . ?

FLANAGAN

—Why do they call me by that name?

ELISE

It’s the way you carry yourself: your hands . . . The way you walk down the hallway: “Saint James.”

FLANAGAN (quiet, at first)

O . . .

(Barks:)

Ha!

ELISE (she laughs too)

. . . You’re not mad?

FLANAGAN

No . . . I may in fact be “mad”—that is, a little off-kilter tonight, Ms. Sanger—but you’re right. —You are absolutely right! Road to Calvary, that’s how I’ve been . . .

(She watches him, closely.

He drinks some more—finishing off his glass.)

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

Bring me those letters, please; I’d like to read them now.

ELISE

Really?

FLANAGAN

Why shouldn’t I . . . ?

ELISE

—You seem—

FLANAGAN

What:

ELISE

—nervous.

FLANAGAN

I am not / nervous—!

ELISE

You are! —You’re afraid they’ll be too sexy.

FLANAGAN

—Too what?

ELISE

Sexy! pissy! / filthy!

FLANAGAN

—Is that what you think I’m / afraid of?

ELISE

—You are afraid! I can tell from here!

FLANAGAN

My dear girl I can assure you I care less what those letters have to say on the subject of “sex.”

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN

. . . I’m curious, that’s all.

ELISE

In one letter she says she wants to make love to him with another woman . . .

FLANAGAN

. . .

ELISE

—You see?—you are / afraid!

FLANAGAN

—It’s a question of taste, my girl! —Morality is a question of taste! . . . And so I simply do not care to speak lightly of that sort of thing. —It’s simply an opinion of mine: I think we all might be a great deal better off were we all a bit more repressed. Shame is a wonderful tool—for good. And I’m talking about the

world here: think of all we might be avoiding, right now, as a culture: —and I know it’s not very popular these days, or for the past twenty-, thirty-odd years—but: there’d be no AIDS, yes?, fewer undesired pregnancies, divorces, molestations. What I’m saying is simply how I feel: “repression” has got a bad rap since Freud. And that’s one very big reason why I won’t read anything written after the First World War.

—My God, we’re obsessed with deviance!—a Godless culture running around with its head and pants cut off. The papers, on TV: you see a new story every day—about priests—. Did you know, last month, the priest from my parish was accused of molesting a young man—a boy, really, seminary, years ago; and this kindly old man walked down to the river—just last month this all came out, in the press, you can read it—and he threw himself into the water—.

—Right into the filthy waves . . . !

. . .

And that boy today who came into my office—he’d been abused.

—I’m sure of it now . . .

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN (gentler; an apology, perhaps)

—And I’m not saying people should never have sex—they should. And it does not have to be a dreary affair; it can be quite beautiful, Elise . . . —Because a little repression goes a long way in making it that much more rewarding when one finally does give in—.

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN (to the books)

I said I know it’s not / popular . . .

ELISE

—Do you really feel that way?

FLANAGAN

About sex?

ELISE

About life.

FLANAGAN (quietly)

. . . You think I’m an old maid . . .

ELISE (smiles)

. . . A what . . . ?

FLANAGAN

An uptight, dried-up old—it’s all right if you think that about me. I think that way about myself / sometimes . . .

ELISE

I don’t think any bad way about you, James . . .

Why don’t you sit down now; okay?

(A moment.

Then he does sit down: lowers himself discreetly into the chair opposite.

He keeps the suit jacket on.)

ELISE (cont’d.)

. . . Take your jacket off now, please . . .

FLANAGAN

. . . Shall I?

ELISE

Yes. You shall:

(He takes his suit jacket off.

—And, turning, drapes it over the shoulders of the chair.

The gun clunks ominously in the suit jacket pocket.

She flinches.

He smiles, takes greater care . . . . . .

Long pause here as he arranges himself torturously without his suit jacket on . . .

ELISE watches: he’s wearing a light brown shirt . . .

She reaches out to him—to remove a thread?

He kisses her. Awkwardly. Forcefully.

. . .

She pulls back.)

FLANAGAN

. . . ?

(She kisses him now. Gentler.

They begin to caress each other; awkwardly.

After a moment or two:)

ELISE

. . . You don’t remember me, do you.

FLANAGAN

. . . From when?

ELISE

Scarsdale. Sorry.

FLANAGAN

. . .

ELISE

I grew up there. —My parents still live there.

(With a sigh, as if disappointed:)

Both of them, still married . . .

FLANAGAN (he pulls away farther)

. . .

ELISE

You don’t remember me, I know you don’t.

FLANAGAN

—Did I have you as a student?

ELISE

(“Yes.”)

FLANAGAN

—When?

ELISE

I don’t know—eleven, twelve years / ago . . .

FLANAGAN

Why wasn’t—? Why wouldn’t you tell me this before . . . ?

ELISE

—When before?

FLANAGAN

—When I interviewed you, last summer—

ELISE

I lied on / my résumé—

FLANAGAN

—at any time in the last six months—. Why didn’t you tell me so tonight?

ELISE

—I just did tell you—. —Does it matter?

FLANAGAN

Of course it matters—! Obviously it / matters—

ELISE

Why?

I mean, there’s a lot I haven’t told you—about me. —You hardly know me—.

FLANAGAN

—Does Richard know?

ELISE

I don’t know. I think so.

FLANAGAN

You think—?

ELISE

Do you remember this poem I wrote?

(He looks at her, full in the face.)

ELISE (cont’d.)

The assignment had been to write a poem about someone you loved, and then lost. —“Loved and lost.” And you wrote about your uncle—how he died in World War Two. —And I wrote this poem about my brother: my younger brother had died a few years before that. An accident . . . I couldn’t write about it yet—well, or honestly. So I made a kind of free-verse rhyming thing, about a crow. And snow. —Those two words rhymed a lot . . . And how the crow flew from a high branch to the snow on the dead grass, then up again, into the sky . . .

You called it trite . . .

You gave it back to me, in class: “Heartfelt,” you said, “but trite.” I had to go home and look that word up in my parents’ dictionary just to find out what you meant about me . . .

FLANAGAN

. . .

ELISE

—And then you asked Brian Sloan to stand up and read his poem. —Do you remember Brian Sloan? He’s a plastic surgeon now; married, two kids. —And, anyhow, in heroic couplets he’d written this really very treacly poem about a grandmother who’d suffered a stroke . . . “Poignant,” you said, to the class, “and true.”

What I remember most about Brian was how he used to tease you in class; and you used to tease him right back. To flirt. The rest of us thought there was something somehow weirdly, vaguely sexual going on—we never said that, out loud, but we felt it . . . And then one day, later, after all that business with the poetry, I came to class early and you and Brian were there, discussing To The Lighthouse; and Brian was sitting on his desk, with his legs up under him. Like this, you know, like he used to—in a really very childlike position—almost feminine, really. —And you also were sitting on your desk! In exactly the same way!—You didn’t think his poem was any better than mine; you liked him more. You wanted to be his friend. You were a boy.

FLANAGAN (shaken)

. . .

ELISE

Do you remember that—?

(He kisses her again—aggressively. After a moment of shock, surprise, she begins to kiss him back.

They continue kissing, groping. He gets his hand up under her shirt. Fondles her, hands shaking terrifically . . .

She takes one of his hands and places it on her thigh, under her skirt. His hand moves higher.

She unbuttons his shirt . . . His pants . . . Her hand goes into his pants.

A moment. . . .

They both have stopped kissing. . .

He stands:)

FLANAGAN

I really should be going.

ELISE

James—

FLANAGAN

I have to get all the way uptown / and—

ELISE

Sit down, James, it’s all right—

FLANAGAN

—No—no, I do not think it is all right, Elise—you see, because: I do not think I should have come here in the first place—

(In throwing his coat over his shoulders, throwing his arms through his coatsleeves:

The gun spills out across the floor.

They both flinch: will it fire?

He bends to pick it up.

He holds the gun for a moment—too long.

He looks at the gun in his hand . . . )

FLANAGAN (cont’d.)

. . . Did you really think I was a pedophile? . . . Is that what you really thought of me?

ELISE

No; I didn’t / mean that—

FLANAGAN

You said that: —“all the children”—all the children thought this thing of me /

(an explosion:)

—a disgusting thing about me—!

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN (holding the gun, still; quiet again)

Are you angry . . . ?

Is that why you asked me to leave that bar with you—because you are still angry that I did not understand an adolescent poem . . . ?

ELISE

. . .

FLANAGAN

Because I was under a false impression here, Ms. Sanger—it’s not your fault.

(He smiles, lips tight.)

Tonight, when Richard was about to say something in front of all those people that I did not want him to say—do you know what it was he was going to say? About me? He was going to say something true . . . He’s the one living person who knows this one true thing about me . . . He knows what is true without knowing the reason for it; —and somehow I feel I ought to tell it to you now. Both what is true, and why. —Or perhaps I should save that for another day . . . when we both know each other better. —Because I like you, Ms. Sanger, I do . . . Elise . . . What a great adventure it has been simply for me to be here with you tonight. To stand here in your presence, in a beautiful young girl’s apartment, in someone else’s apartment that is also your apartment, browsing through books and talking—enjoying such wonderful conversation, even when we have felt compelled to discuss quite serious or morbid things. I have never been with a woman. In all my adult life. I have never been on intimate terms with a single other human being in all my sixty-five years. Because of one incident in my youth.

How cliché, you might say, Ms. Sanger . . .

. . .

I am sorry I did not understand your poem.

(She stands still, not knowing what to do.

She holds out her hand—for his hand, or for the gun, perhaps.

After a while, he takes the gun and replaces it gently in his pocket.)

Contributor’s

notes

return to top

|