Peter Taylor: The Basement Tapes

The following interview with Peter Taylor took place at his home in Charlottesville on November 3, 1988. The article was set to appear in 64 in July 2002. That issue was set in type but never published.

|

|

| Peter Taylor | |

Peter Taylor couldn’t drive after he had a stroke in the mid-’80s, and I once chauffeured him and his wife, Eleanor, from Charlottesville to a reading in the Northern Neck. We took the scenic route back and wound up at Westover Church in Charles City County. The Taylors happily explored the beautiful old church and adjacent graveyard. A huge, friendly dog wandered over from a nearby house. By the end of the visit he became so enamored of Taylor that he leaped into his lap before he closed the car door. We all had a good laugh after they were disengaged.

That image of Taylor laughing—enjoying himself immensely in a rich historic setting—is usually the first memory that comes back when I think of him. In some ways it’s emblematic of who he was. Wonderful in conversation, he said things in class and in conference that shaped what I think about writing. But I always go back first to how much fun he was—bright-eyed, telling story after story—and how much life he brought to any group he was in. Last year’s biography, Hubert H. McAlexander’s Peter Taylor: A Writer’s Life (Louisiana State University Press, 2001), quotes family friend Mary Jarrell, who remembered that, even after a hot afternoon spent working outside on one of his many projects, Taylor always appeared “showered, flannelled and radiant; in love with the party, and hoping it would last all night.”

Invariably pleasant, he could also be profound. He sometimes had a life-changing effect on those he encountered. Charlottesville writer John Casey was studying at Harvard Law School when he took a writing course from Taylor. “Don’t be a lawyer, be a writer,” Taylor told Casey after reading his work. Casey took his advice, producing a series of critically acclaimed novels (his latest, The Half-life of Happiness, was published in 1998).

Richmonder Lawrence Reynolds took writing courses from Taylor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. But he considers even more valuable the time they spent restoring an old cabin called Hornet’s Nest in Southwest Virginia: “Peter became my father, my brother, my second self.”

Reviewers were equally moved by Taylor’s work. A characteristic accolade from writer Anne Tyler: “He is, after all, the undisputed master of the short story form.” An even more unqualified assessment came from Jonathan Yardley in The Washington Post: “He is, in his seventy-sixth year, the best writer we have.”

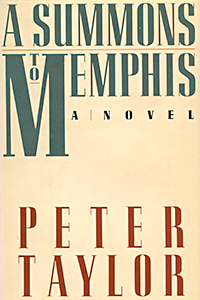

When Yardley wrote that, in 1993, Taylor had been publishing fiction for fifty-six years. A frequent contributor to The New Yorker in the years following World War II, he was also a mainstay of the nation’s best literary magazines, including The Kenyon Review, Sewanee Review, and The Southern Review. There were prizes, like his 1978 Gold Medal for the Short Story awarded by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Yet he remained a relatively obscure writer’s writer until he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1987. Ironically, it wasn’t for a collection of the short stories that are considered his masterpieces, but for a novel, A Summons to Memphis.

He took the fame that came late with a grain of salt. Once, I was sitting with him before he read, the introducer going on earnestly and too long about the Outstanding Accomplishments of the Great Man, and he leaned over and whispered, “Yes, yes—I’m a national treasure.”

His stories are set almost exclusively in the upper South of his Tennessee upbringing. His characters are usually upper-middle or upper class, often telling a story that seems polite and genteel on the surface, yet beneath there is layer upon layer of meaning that’s anything but. With such a milieu, the label of “regional writer” was inevitable—but it never stuck. Taylor’s Tennessee is as universal as Faulkner’s Mississippi.

Still, he was quintessentially southern. I treasure an anecdote he told a graduate writing class about leaving a teaching position at Harvard because of a June snowstorm: “It was just too much!”

It would be hard to imagine a richer background for a writer than Taylor’s Tennessee childhood. Family stories included tales of a grandfather, Bob Taylor, who defeated his brother Alf in the 1886 race to become that state’s governor. After serving three gubernatorial terms, “Our Bob” was elected to the United States Senate in 1907. He was much beloved. When he died, thousands came to the railway stations to mourn as the funeral train bore his body from Washington to Knoxville. That funeral train was at the heart of Taylor’s final novel, In the Tennessee Country, which he was working on during this interview. It would finally appear just months before his death on November 2, 1994.

Another grandfather—also, interestingly enough, named Bob Taylor—was kidnapped, along with his law partner, by Klan-like outlaws called Night Riders. He escaped while his partner was being hung, dove into Reelfoot Lake, then hid out for days in a swamp. This incident forms the basis for the short story, “In the Miro District,” which can be found in the 1977 collection of the same name. In an unquoted part of this interview, Taylor said he thought it was his best story.

|

|

| Peter Taylor at Kenyon College | |

Attending first Vanderbilt, then Kenyon College in Ohio and Louisiana State University, Taylor formed enduring friendships with some of the best literary minds of the twentieth century: John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, Robert Lowell, Randall Jarrell, and others. He married the poet Eleanor Ross in 1943. She continues to reside in Charlottesville. Her most recent book of verse is Late Leisure, published in 1999.

Like many others in central Virginia, I knew Taylor first through his fiction writing classes at the University of Virginia. We met when he taught creative writing to graduate students in the late ’70s. Ten years later, Taylor was a guest on a public radio series I hosted called Virginia Writers.

It was both a good and a bad time for Taylor. The Pulitzer had brought a wider readership and some measure of celebrity. He was working productively, yet health problems were a continuing concern. His speech was slurred by the stroke, which made transcription of the tape difficult. And he had a new granddaughter, Mercedes Kelleher, born to his son Ross and wife Elizabeth just a month before I interviewed him in Charlottesville on November 3, 1988.

I started the tape in the hallway leading to his basement study while Taylor was talking about the framed photographs of the houses he and Eleanor had restored. “I have an obsession with houses,” he said. The couple owned some two dozen in their fifty-one years of marriage, sometimes working on several at the same time. Once, they even bought a favorite house twice.

Peter Taylor: This is a little house we had south of town we call “The Ruin.” A little eighteenth century house that I salvaged. This is the house we had at Sewanee [Tennessee]. It was a former chapel. It had been changed and made into a cottage.

Ben Cleary: Did you have the same proportion of wicked thoughts living in the chapel?

PT: [Laughs] More.

[He moved on to photos of family and friends: his parents’ golden wedding anniversary, John Crowe Ransom’s eightieth birthday.]

PT: And this is from the Tower of London. This man from British Broadcasting stopped to interview us and I began telling him about what I was doing—my literary activities. He wasn’t interested at all. He’d just picked us as typical tourists.

[We settled in his study.]

BC: The houses in your stories—I often get the feeling that it’s all the same house. Can you talk about that?

PT: I suppose that the houses are the houses of a domesticated people. And in that sense they’re all the same. I’m not very much aware of the houses. Afterwards I see that I’ve been describing a house or concerned with it. The first one that comes to mind is [in a story] called “Porte-Cochère”—I forget the title I give to a story finally because I usually give it about ten titles while I’m writing it. That is about a man whose study is out over the porte-cochère [a large porch] in this big Memphis house—it opens off the stairway off the landing—and when his children go upstairs or come down they have to pass by the door to his study. And in a way he’s controlling or watching them constantly and that’s his relation to them in terms of the house and in life, too.

I remember the real house I based it on. They kept jam in the basement. They also kept wine and one of my aunts would make the little servant boy whistle the whole time he was down there to make sure he wasn’t into the wine. I think maybe I bring that into that story.

One of the things that I’ve thought to myself in recent years: so many people say my stories are about quiet people who have quiet ordinary lives—middle class people—and that generally is the setting of most of my fiction—husbands and wives and their children and so on. It’s been remarked on as being different from other stories in that way. But everything is by contrast in fiction. The only way these people can be made to seem quiet and to have quiet, uneventful lives is to put them against people who are more eccentric and who are more gothic.

Another side of it is this aspect: if there are violent things in the stories I often have to first try to see how they can be presented in terms of the quiet everyday lives that we live. To me the story that begins with horror and goes on to horror to horror is not nearly as effective—I don’t like it as much—as one that seems to be telling a very quiet story of domestic life.

[We talked about characters in several of his stories. I brought up an African-American couple in “Bad Dreams,” a story from his 1954 collection, The Widows of Thornton.]

PT: I was trying for certain effects in that and it’s been awfully interesting to me the way different people have responded to it. The one I’ve liked best has been [that] black people who have read it—good writers for whom I have great respect—have liked that story particularly and that pleased my ego because I felt that I entered into it [their lives]. I was interested in them as human beings and not as black servants. In the end it’s really a story about their humanity and not just their color.

I grew up so much with black people like that. I didn’t think of them as something exotic or strange or different. My family would leave the country and leave us with [them] and I turned to them for all sorts of support and comfort when I was a child. Even my first interest in painting and being an artist—I would talk to them about it more than anyone in my family. And so there was a closeness there that I didn’t have with my actual family, I think.

BC: I’ve read a quote from you that during the years of integration you turned away from writing about black people. Why was that?

PT: My feeling is that when war breaks out you can no longer be objective and you get very sentimental and you’re writing slogans and you’re trying to prove that blacks are being mistreated and there’s too much emotion and prejudice there. Whereas when you’re not in the midst of the fray you could be cooler and more objective about it. Gertrude Stein said to me during the war [that] she didn’t worry about the blacks anymore: “They’ll take care of themselves now. They’ve come to the point where they can take care of themselves. I can think about other things.” Well that’s not entirely true, but once the cry was taken up and the battle was . . . engaged—well, then it was no longer the time to write. Just as, during the war, you didn’t write about—or if you did write about—love of country [or] anything of that sort you were apt to get rather maudlin and overdo it. And I felt that I’d had my say long before the rest of the world was saying what they were about integration and such things.

BC: Do you have any writer’s superstitions? Rabbit’s foot in the pocket, certain times of day?

PT: Oh, I used to. I wrote my first stories sitting on the porch swing at home when I was very young and for years I felt that I couldn’t write unless I was on that porch swing. Or I was on a swing or on a rocking chair. But I overcame it. I really can write in almost any circumstances now. And when I’m traveling or when I’m at home I get so completely lost in it so fast that it’s more real to me than anything.

BC: Times of day?

PT: I usually, just because I think it’s a sure thing, I usually say I work every morning and I reserve most mornings to writing. But sometimes once you get a story going and it’s going right you can write ’round the clock. Sometimes at ten o’clock at night I’ll come downstairs and start writing. I just say the mornings because I’m fresher and I want to give my best hours to writing and so I do that. I think it’s bad to write [for] too long. It is for me, to write too long a period. After I’ve written about three hours it’s better [to] stop because I start to make mistakes after that.

[The conversation moved on to teaching as a profession for writers.]

PT: I learned so much from older writers when I was young. It was a very personal thing . . . I met Allen Tate in Memphis [and] he persuaded me to go to Vanderbilt to study with Ransom and Donald Davidson. I remember I went to Vanderbilt the first day to register in old Kirkland Hall and Mr. Davidson was registering and I told him that I had come there because of Allen Tate and he took me over and introduced me to John Crowe Ransom and said, “John, this is the boy Allen has sent us from Memphis.”

Well, that was a very personal, warm sort of entrance into the literary world and that’s been my experience. I never like to think of myself as a professional writer in the sense that I don’t believe I want to turn out a book every year or every two years or anything like that. I think you have to write as a poet would write about his mistress or his country or something. A story writer writes out of a compulsion to paint a picture of the world he lives in and for the satisfaction it gives him, not for the glory and fame—that you may want also—but that is not the best motive. I like to think that I’m not professional, that I’m not going to do certain things to advance my career. Teach school, become a librarian, do something else and then let your writing be its own master.

BC: You’ve always been a writer’s writer in so many ways and fame has come late. Was there ever a point in your life when you saw a way you could turn your fiction to make it less artful and more popular and did you ever waver in that crossroads?

PT: Well, I didn’t think very much, because it was so much more fun to do it in a serious way than to try to make a career of it and I was willing to sell real estate or anything to make my living and to support my family. But my writing was sort of my religion and I didn’t want to become more popular. One thing that supported me, though, and made me able to steer an independent course, more or less, and to take this unprofessional view is that I had so many writer friends who I knew were the best literary minds in the country. There was Tate and Ransom and Robert Penn Warren and Katherine Anne Porter and Andrew Lytle right at my side from the time I was a boy on. And my roommates and friends were Randall Jarrell and Robert Lowell. When I had their support and admiration as a writer it was a lot more important—and still is—than having a wide popular appeal.

I say that, though sometimes it’s very easy in retrospect to go back over your life and make it all come out even in the end. I didn’t suffer inordinately. It never really occurred to me very much. In fact, when we were young it seemed rather vulgar to be too successful.

BC: Anything you want to add?

PT: Lucking into that literary group early on—it was immeasurable the good it did me. And how it has supported me through all the years of being a writer. Also, I never would have been satisfied to become a teacher if I hadn’t known all these wonderful writers who were teachers. I think partly they became teachers because [it was during the Depression and] there wasn’t the pressure; anybody would jump at anything they could make a living at, so I followed in their footsteps. Again, it has given me a certain freedom to write as I pleased, knowing that I was earning my living teaching. To begin with I earned my bread that way and I was free to write absolutely as I wanted to and not involved in becoming a success.

But, as I say, these are afterthoughts. Sometimes I’m suspicious. As Hemingway says, he doesn’t trust people whose stories all fit together too neatly. I mean, about their lives. It’s easy afterwards to think, “Ah, I did it this way because of so and so.” A lot of it was just hit or miss—luck, it turned out.

|

|

It was just so much luck. After the war, when I came home from overseas, my wife and I went to visit Allen Tate at Sewanee [The University of The South], and he told us we ought to go and live in Greensboro and I should teach there. So he talked to somebody there and I went over and talked and it was all so easy. I’ve had such an easy time of it always. I tend to forget and think I’ve made my way pretty well but it’s all been luck from the beginning.

BC: Do you have a projected date for the piece you’re working on?

PT: I really do think it’ll be three or four years yet. [Laughs] It’s too bad but that’s the way I’ve always written—so slowly. One of the joys of it is taking it easy and not feeling that I ever have to finish it up to keep my name before the public or anything. It’s the greatest pleasure in life. The greatest satisfaction is doing this, writing fiction. And so I don’t want to destroy it. That’s what I live by now and I’ll just wait on it.

[In the Tennessee Country actually took Taylor five more years to finish. It was completed toward the end of 1993 and published just three months before his death on November 2, 1994.] ![]()