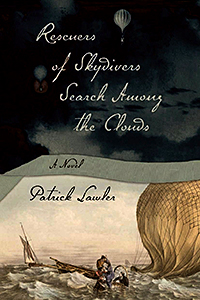

Review | Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, by Patrick Lawler

University of Alabama Press, 2012

|

Readers of Patrick Lawler’s first novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, can look forward to a treat—but only if they can divest themselves of the current (and, to my mind, lamentable) divide between poetry and fiction. This is certainly not the first attempt by an author to bridge this gap—one fine example of a writer working in this vein can be found in Anne Germanacos’s In the Time of the Girls, (reviewed in Blackbird v10n2)—fiction which uses a loose verse format and poetic structure to create startlingly arresting story images. In spite of examples such as this, however, readership and authorship for poetry versus fiction have certainly become more divided during the twentieth century, and do not seem to be moving closer in the twenty-first; therefore Lawler’s masterful way of simply ignoring the constraints of either, while incorporating the best of both, is all the more welcome. Lawler takes the blending of poetry and fiction to a new level in his work, an achievement for which he has won Fiction Collective Two’s Ronald Sukenick/American Book Review Innovative Fiction Prize.

Those who have a traditional notion of the novel may at first find the structure confusing. Lawler titles his chapters with sentences that could serve (and sometimes do) as the beginning of the actual text (the first is entitled, “My Mother Walked Down Joy Boulevard. My Father Was A Beekeeper.”), which itself defies linear structure by going to and from particular themes, mixing references to people and places, so that the reader gets an almost collage-like impression of the sentences and even words, as if the author wrote a very loose description of people and events, and then cut them up and rearranged them to create new and sometimes startlingly lovely combinations. The narrator opens the book with a seeming-explanation of the name of the chapter, which also works as an introduction to the place:

That year the mayor decided to name the streets after presidents who had been assassinated. He was never satisfied. According to him a town’s character was written across it in the names of its roads. Once the streets were named after berries, so we walked down Choke Cherry Lane or Elderberry Road or Raspberry Way. These names gave us places to live our lives. Girls could be lusted after on Strawberry Street. Boys could smoke cigarettes, watching clouds of hair from the corners of dark red/blue intersections. The mailman would lug his bloated bag down Boysenberry. . . . The mayor made a conscious effort to select the edible berries though some poisoned ones slipped in—which led him to go with the assassinated president idea.

This opening, though it appears arbitrary and fanciful, actually does a thorough job of depicting the kind of place we’re to inhabit throughout the book—a small town where families and civil servants live their typical lives, made extraordinary through Lawler’s fantastical invention.

In the second paragraph of the first chapter, we’re introduced to the narrator’s family:

When I was born they named the streets after emotions: my mother walked down Joy Boulevard. My father was a beekeeper. Almost robotic among the bees with his smokepot and his bee clothes, almost feminine with his netted face. I spent my childhood with bee stings. My mother was a hagiologist studying saints. My sisters would spend afternoons digging for relics in the backyard. The bees were ambassadors from an ordered and enchanted world. They were scholars obsessed with an ideal, always returning to the same roundish, yellow perfection of their lives. Flying alchemists. . . . It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth.

In these opening paragraphs, possibly the most linear of the entire book, Lawler mostly connects ideas one after the other, rather than scrambled and reordered; yet because of the images that he has chosen, we get a strong sense of the wonder of childhood, and the magic that surrounds young families in their everyday settings.

This opening also contains the beginning of one of Lawler’s favorite tricks—to open sentences with the same phrase repeatedly, always adding a new phrase to complete it, so that “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the sky or lived in the earth” after the description of the bees, becomes “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the story or lived in the words,” after “One day I wrote a poem and my mother sprinkled holy water over everything”; and then, “It was impossible to tell whether we lived in the filled or lived in the empty” following “Years later my father became a bee sipping from an aluminum flower. . . . I called the family together for the Magic show. I didn’t have a veil big enough.” This new convention of Lawler’s gives the impression of a child’s-eye view, a narrator young enough to want to explain the workings of his family and life, but not old enough to understand that he can’t make a new rule every time he opens his mouth. The reader comes away with a new kind of understanding—of course you can make a new rule about families every time you discuss them; their true nature, Lawler seems to be saying, shifts sneakily every time you look.

The mood of the chapters progresses from the uncomplicated happiness of a young family (“My mother always felt something really good would happen. . . . Mostly we ate honey”) to something more complex (“Part of the problem was we couldn’t distinguish between a dream and an egg. That was the year we kept losing things”), as Lawler develops a new convention—the repetition of particular iconic symbols, paired with various ways to interpret them:

“Words hurt,” said my Grandmother.

“Words hate us,” said my brother.

Standing in front of my Grandmother’s bookcase, I felt the vibrations and hunger. Each book nudged its way into the next book—one book being eaten by another.

“Words collect in the corner of the mouth,” said my older sister.

That was the year there was an accident in the library, and we were thankful we lived next to a mirror factory. . . . A man who was in the library accident was buried under classics. When they tried to rescue him they started drilling down through the books and lowering mirrors to see if there was any breathing. . . . In the library they tried to yank the man out from under the words, but it was futile.

Here Lawler’s repeated interpretations use the literal child’s-view perspective to explore the way books and words affect us—in the world that Lawler creates, they have the power to cause physical damage. In contrast to the seriousness of the literal situation here, Lawler also uses this youngster’s point of view for sly humor quite often—we know that there is a double meaning, which often creates a delightful inside joke between author and reader.

The images to which Lawler chooses to return seem to be chosen by a child, trying to make sense of his immediate surroundings—birds, the sky, the neighbors, what he learns in school, the various (and telling) occupations of the father, the moods and preoccupations of the mother, what the TV said, what he ate, the relationship between the house and the cellar; but Lawler takes these commonplace observations and makes them both remarkable and somehow truthful:

For school we had to make a list of things we were afraid of. My list included:

ELECTRICITY

FACTS

BREATHING TUBES

GETTING CAUGHT . . .

The TV said: Look at the pretty. The TV said: There are no consequences.

The TV said: Worry. . . . That was the year our neighbors gave their children away. Garage sales everywhere were filled with doll clothes and broken appliances and stone clocks with garnet gears. . . . If you looked deeply into the cellar you could see a crater where the heart of the world had been taken . . . In school I learned there would be transition stories—stories between the old stories and the new stories. . . . I had forgotten how to read.

When Lawler strings together these seemingly arbitrary associations—learning about fear in school, conflicting messages from the media, neighbors’ strange goings-on, and the fear of the cellar—in his looks-random-but-really-very-purposeful way, he forms a new atmosphere, a tone that we somehow recognize from our own childhood, and maybe adulthood, too.

These images and many more reoccur throughout the short, fragmented chapters, and the various combinations they form indicate the growth, struggles, and tragedies, small and large, that the novel’s family undergoes. Gradually, plot emerges, and the themes begin to grow up along with the narrator: “The Since girl talked to me after class. Gravity had already memorized her body, and I ran out of things to say. I could feel a hook inside my heart.” And, “That was the year I listened to my parents having sex. . . . Sadness followed my father home. That was the year I saw a woman lying on a grave—crying. . . . That was the year I kept hearing my mother say no.” And, in a chapter called “At School I Write a Story Called ‘Genitalia,’” “That year the boys in school tried to look up the skirt of the However Girl.”

Lawler does well to contrast these relatively lighthearted images about sex with the darker, more adult side of the same theme:

After our father left, my mother kept putting up warnings around the house.

If you ever get thrown in the trunk of a car, kick out the back tail lights and stick your arm out the hole and start waving.

After my father left, I heard one of my aunts say to my mother, “That’s just the way men are. If he’s not thinking about yours, then he’s thinking about somebody else’s.”

That was the year the household went through considerable amounts of Kleenex. . . .

My uncle said,

“I’ll tell you how to treat a woman.”

“What about our aunt?” my brother and I asked.

“She’s a wife,” he said.

“I think it has something to do with flowers,” said the Latin teacher.

Lawler’s seemingly artless way of arranging the less and more sinister problems associated with sex side by side with each other not only sets up another, and darker, inside joke for the reader to understand and appreciate, but also allows the reader to see how sex, as well as other difficult family issues, can be both delightful and terrible, and to feel the power of each iteration.

When we read traditional fiction, we can easily see the difficulty in ordering details of plot, development of character, the continuation and deepening of themes, and making it all interesting. In Lawler’s novel, his ability to make the arrangement of the sentences appear to be happenstance, while at the same time coaxing poetic meaning out of their order, makes Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds particularly distinctive. His technique of skillful experimentation with the ways apparently unrelated phrases and ideas can be connected yields a new and oddly truthful meaning for each; the reader feels the emotions of the characters and understands how they suffer, and why it’s important.

Patrick Lawler has published of three collections of poetry: Feeding the Fear of the Earth; A Drowning Man is Never Tall Enough; and (reading a burning book). All three have been praised as groundbreaking for the fearlessness of the subject matter and the unlikely gatherings of characters. In Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds, Lawler has taken his unbounded sense of what can be done with words and ideas a step farther; in creatively and successfully combining the conventions of both poetry and fiction in one book, and having the temerity to call it a novel, Lawler accomplishes another step towards what should be happening throughout the literary world—the undoing of genres. ![]()

Patrick Lawler is the author of one novel, Rescuers of Skydivers Search Among the Clouds (University of Alabama Press, 2012). He is the author of three collections of poetry, Feeding the Fear of the Earth (Many Mountains Moving, 2006), which won the Many Mountains Moving poetry competition, (reading a burning book) (Basfal Books, 1994) and A Drowning Man is Never Tall Enough (University of Georgia Press, 1990).