continued from v17n2’s “Everywhere in the Kingdom”

continued to v18n2’s “Enough of Us Still and Brave Enough”

What Was Not His to Keep

| Willa Cather from One of Ours Ethel Anderson Frances J. Grimké Richmond Times-Dispatch Richmond Planet Richmond Times-Dispatch |

||

He looked up wistfully at his Lieutenant as if to ask him something. His eyes filled with tears, and he turned his head away a little.

“Mein’ arme Mutter!” he whispered distinctly.

A few moments later he died in perfect dignity, not struggling under torture, but consciously, it seemed to Claude,—like a brave boy giving back what was not his to keep.

―Willa Cather, One of OursThis past week has been dreadful. How little ten people could do caring for 1,400 boys wounded and medical cases. Influenza has been playing mischief. The poor boys have been walking into the hospital and are cyanotic when they come, and although everything is done for them, many have gone “West.”

―Ethel Anderson, from Under the Red Cross

Flag at Home and AbroadDuring these terrible weeks, while the epidemic raged, God has been trying in a very pronouncedly conspicuously and vigorous way, to beat a little sense into the white man’s head . . . What does the lightning, the thunderbolt, the burning lava, the sea, care about color or race?

―Frances J. Grimké, “Some Reflections”When the influenza epidemic struck Richmond, Dr. Flannagan was Chief Health Officer and every force in the city was put into play by his office to check the spread of the disease and to treat those suffering with it. John Marshall High School was turned into an emergency hospital for white patients and Baker School for colored patients.

―Richmond Times-Dispatch, “Director Levy Is

Taken to Task by Flannagan.”

In the course of seeking out work about the 1918 influenza pandemic across two issues of Blackbird, we have discovered poignant accounts from both historical and fictional individuals.

Ellen Bryant Voigt’s 1995 book of sonnets, Kyrie, long known to us, and Bryan Bouldrey’s recent 2018 essay, “One Singer to Mourn,” are central to part one of the 1918 Suite—“Everywhere in the Kingdom,” titled from a line in Voigt’s Kyrie.

In this issue, part two of the 1918 Suite, “What Was Not His to Keep,” takes its title from a passage in Willa Cather’s 1922 novel One of Ours.

Book four of Cather’s novel—which we excerpt here—follows Claude Wheeler, the young midwestern protagonist, on his jouney to France by troopship during the first World War. (Cather based the protagonist Claude on her nephew, G.P. Cather, who was killed in the war.) Just days after waving goodbye to the “Goddess of Liberty” in New York Harbor, Claude and his fellow soldiers face an unexpected onboard outbreak of influenza.

|

| Troopship leaving New York. c. 1918. National Archives. |

Despite being awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1923, One of Ours was panned by her contemporary male critics such as Sinclair Lewis, H.L. Mencken, and Ernest Hemingway. Literary scholar Daryl W. Palmer (“Ripening Claude: Willa Cather’s One of Ours and the Philosophy of Henri Bergson”) writes

Nearly seventy years after its publication, the novel continued to breed binary and bellicose oppositions. It was either idealistic or realistic, either romantic or ironic. Was was either good or bad. Cather was either ignorant or savvy. Claude was either a fool or a hero.

Palmer defends Cather against the critics of her time, asserting, “Far from offering thoughtful appraisal, Hemingway and his compatriots were intent on guarding male territory.”

Cather is known to have relied heavily on two sources for this section of the book, notably the war diary of a doctor she met while being treated herself for influenza in the summer of 1919 in Jaffrey, New Hampshire. Fredrick Sweeney, formerly assigned to an American Expeditionary Force troopship, apparently loaned his diary to Cather without understanding the degree to which she would depend on it for the novel.

Sweeney’s diary, to this day, has not been published or digitized; one must travel to physical archives to examine it or copies. We can’t help but wonder if it would have remained only with the family if not for Cather’s use of it. Might it have languished in a box of papers, or been lost or destroyed? The ethics of the use of the diary aside, the novelist here preserves and magnifies details of an individual’s view of history that might otherwise have been lost.

|

| 1921 funeral after the body of G.P Cather is returned to Bladen, Nebraska. Cather was killed June 25, 1918 and was first interred in the military cemetery in Villers Tournelle, France. |

Lost, found, or redisovered narratives continued to surface in our research. Ethel Anderson’s diary and scrapbook, Under the Red Cross Flag at Home and Abroad relates the experience of nurses in World War I and the journey of the members of Evacuation Hospital #5 across France after leaving from Philadelphia in a convoy of ships in July of 1918. Anderson’s scapbook is fortunately available through the New York Library’s digital collection; we know little of her other than what is revealed in this singular collection of text and photographs.

Anderson rarely speaks to the discomforts and horrors of war nursing; she uses a more restrained, make-the-best-of-circumstances tone yet still provides a moving account, generous in its descriptions of camaraderie and humanitarian mission.

A photograph of the tents that serve as quarters for the nurses appears adjacent to a passage in the scrapbook describing an aerial night attack on the nearby town and the deployment of antiaircraft balloons, “like huge elephants with big floppy ears.” The tensions are present even when Anderson mutes the volume of her prose, tending, as here, toward understatement:

If you ever have heard the motor of a German plane you are not apt to forget the sound in a hurry, neither the sound of a bomb whizzing through the air. This morning we picked up pieces of shrapnel in the campground.

We close the excerpts from Anderson’s scrapbook with a September 25, 1918, entry on an influenza outbreak among troops in Vaubecourt, France, where she is one of only ten nurses caring for 1,400 “wounded and medical patients.”

Stateside, there were already cases of influenza in Philadelphia when, on September 12, 1918, the city’s public health director Wilmer Krusen went ahead with a planned Liberty Loan Drive parade. 200,000 people attended. “Within seventy-two hours,” according to Kenneth C. Davis (“Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu”), “every bed in Philadelphia’s thirty-one hospitals were filled.” 2,600 deaths by October 5 rose to a total of 4,500 deaths by October 12. The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia provides even more shocking totals:

The pandemic hit Philadelphia exceptionally hard after sailors, carrying the virus from Boston, arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in early September 1918. In a city of almost two million people, a half a million or more contracted influenza over the next six months. Equally as startling, over 16,000 perished during this period, with an estimated 12,000 deaths occurring in little more than five weeks between late September and early November 1918.

|

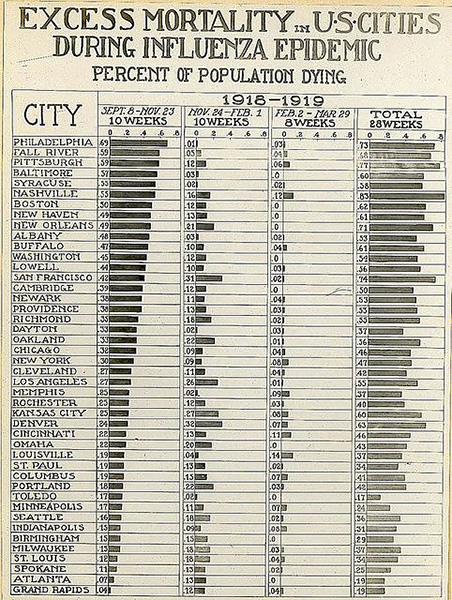

| Excess Mortality in U.S. Cities During Influenza Epidemic, 1918–19 The Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine. |

“‘Some Reflections: Growing Out of the Recent Epidemic of Influenza that Afflicted Our City,” written and delivered by Frances J. Grimké is mentioned in the March 1919 issue of NAACP’s The Crisis simply as one of three pamphlets of which the magazine was “in receipt.” The city in question is Washington, D.C.

This brief mention of Grimké, one of the founders of the NAACP, led us to the text of his sermon published in this pamphlet, delivered on November 3, 1918, at Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church; this was the first Sunday that Washington, D.C., churches opened after being closed, along with schools, theaters, and movie houses, just a few days into October. Notable in the sermon is not only Grimké’s commentary on the pandemic in the historical moment, and the retrictions that brought parts of life in the city to a standstill, but his powerful commentary on prejudice, race, and race relations in 1918 America:

Another thing that has impressed me in connection with this epidemic is how completely it has shattered the theory, so dear to the heart of the white man in this country, that a white skin entitles its possessor to better treatment than one who possesses a dark skin.

In Richmond, as in Washington, D.C., the health director closed public venues in the first week of October, an act that may well have saved lives. Richmond, too, was slated to lift its restrictions on November 3, but not before the city health director, Roy Flannagan, controversially wobbled on that decision as local business owners strongly protested.* Richmond ultimately reopened closed venues on Monday, November 4, 1918. All in all, Richmond and D.C. faired well by comparision to Philadelphia.

While we have no literary texts from Richmond or Richmond writers referencing the pandemic, we offer two newspaper articles from 1918 that give a sense of the pandemic in the city of Richmond,

and a third from 1919 that speaks, pointedly, to stories lost when the health director who replaced Roy Flannagan failed to publish the whole of Flannagan’s submitted report. We share Flannagan’s distress, a hundred years later, at the loss of more than half a dozen accounts by those who served in the temporary Baker School and John Marshall High School hospitals. ![]()

*Though it is generally not our practice to link out to texts that we cannot reprint and preserve in our archives, The Influenza Encyclopedia’s Richmond, Virginia entry provides a thorough historical account of the pandemic in the city of Richmond that we recommend. The Influenza Encylopedia is a project of the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library.