print preview

print previewback WESTON MORROW

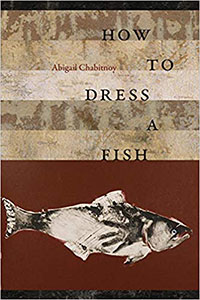

Review | How to Dress a Fish

Abigail Chabitnoy

Wesleyan University Press, 2018

|

There is a certain Homeric feeling that pervades Abigail Chabitnoy’s poetry collection How to Dress a Fish (Wesleyan University Press, 2018)—an Odyssean quest for something called home. Throughout Chabitnoy’s collection, as in the Odyssey, the sea serves as both obstacle and vehicle to homecoming. Indeed, Chabitnoy’s quest is an epic undertaking: the speaker, throughout these poems, attempts to reach into a lost past, find the fraying break in a family line, and suture this long-standing rift.

Particularly given the scope of Chabitnoy’s debut, the term “collection” applies only loosely; the poetic sequences here often flow together and fracture without simple delineation. Throughout the book, at times, sequences blur together without clear titles, separated instead by small, typeset images of salmon vertebrae. Many of these sequences bear no titles, so as one progresses through the text these poems appear not so much as individual, self-contained elements as they do bones in a long, fractured spine. This blending underscores the mosaic strength of Chabitnoy’s writing, as each segment adds to the narrative whole without overwhelming the other constituent parts.

How to Dress a Fish is not only a historical reclamation—a rewriting of inadequate histories told only through a colonial voice—but also a personal reclamation, as Chabitnoy investigates a past from which her family had been separated. The fish spine recollects both the cultural and familial, the speaker of the collection reassembling history as she works her way back, both chronologically and spatially, toward a place that once was home. At the back of the book, in “Ways to Skin a Fish: A Genealogical Survey,” Chabitnoy contextualizes the family history and relocation in 1901 from the Aleutian Islands and Kodiak to Pennsylvania when Michael Chabitnoy, orphaned, was sent to attend Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a boarding school in Pennsylvania.

Through Michael’s separation from his home and the ensuing separation of his descendants, Chabitnoy investigates the impact of the profoundly racist Indian boarding school system, which sought to remove all aspects of the students’ culture until they were fully assimilated, taking their language from them. In “[boy, bear, bird?]” Chabitnoy writes, “What’s behind your back? What was in you(r) hands? feathers, fur or teeth?” She looks back at the widening ripple effect of this assimilation and erasure as it impacted her own life, a symptomatic loss of knowledge regarding her own family’s ancestry. It was not until 1971—when the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act became law, legally enshrining land claims to Alaska Native regional corporations and shareholders who could prove ancestry—that Chabitnoy’s family was reconnected to a lost heritage. But once severed, as the book’s poems and overarching structure proves, these ties are not so simply remade. In “Collection Object,” she writes:

I hide my inheritance behind my back

swinging pendulum

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I am looking for the body

hanging

round my neck

pulling

me

for ward

to the place I

can see honestly, say,I am not an Indian

not not an Indian—

Ultimately, these personal and cultural narratives intersect in the character of Michael. The book’s first section follows the speaker’s attempt to discover her past through this single link, this “Grandfather, Father, Son, Brother. Appealing Outside Mystery.” In “Distance of Articulation,” Chabitnoy writes, “When letters are lost / I think of you, Michael, alone / on a train and dressed / as an ordinary parcel / an acceptable body.”

The second section shifts away from Michael to focus more closely on the speaker’s own identity, weaving fragments of mythic and personal origin, before the book returns to history in its third section, connecting Michael’s fragmentary existence in government records, the speaker’s identity, and the ways in which “origin” may be a collision of both idea and story. All these threads come together in the book’s addendum, a more direct patching of holes in the speaker’s cultural and family history, which reclaims and reasserts a family history that had been fractured and partially erased. In “How to Make a Memorial,” Chabitnoy begins, “These are the facts.” In this final section, Chabitnoy takes the fractured historical and familial narrative and begins the painstaking labor of filling in the holes cut through it both by violence, erasure, and false narratives.

The title, How to Dress a Fish, serves as fitting signal for the book’s scope, interrogating both the way clothes and masks may subvert or alter identity as well as the speaker’s attempt to reconnect with her Unangan and Sugpiaq heritage:

I never learned to sew

or gut a fish.

I didn’t understand how to use the objects

archaeologists uncovered—

Where is my shovel?

Iksak ipegtuq

Siilaq ipegtuq

Mingqun kakiwigmi et’uq

There is a desperate attempt to return—to weave back in one’s missing past—but at the same time the speaker doesn’t know how to do so, or if such a thing might even be possible. As the Alutiiq lines here demonstrate, “The fishhook is sharp / The awl is sharp / The needle is in the sewing bag.” The tools may be there, but the speaker is unsure how to use them and wonders if she can hope to use them to stitch together a hybrid identity.

The reclamation of history and of language are threaded together—the theft of language and of voice occur together, as do the reclaiming of language and voice. Like the poet Joan Naviyuk Kane, who often writes and translates between Inupiaq and English, Chabitnoy’s poems at times dip into Alutiiq. But unlike Kane, whose use of Inupiaq is commanding and assured, Chabitnoy’s inclusion of Alutiiq language in her work is tentative, searching, unsure—and purposely so—seeking a meaning and connection within these words, which the speaker feels both drawn to and separate from:

Engluq nikiimek patumauq

The wrong tongue

By the time you read this

I will have forgotten how to say

the house is covered with sodor home

Language, as well as imagery—the way we are portrayed, displayed, laid out on a page—matters to our existence. Chabitnoy has noted, in a November 2018 interview in Colorado Review, that an older version of her manuscript included a number of long lines that needed to be recut to fit the trim Wesleyan had for the book, a change that caused her some initial consternation, considering her statement in the poem “Collection Object,” “It matters where we break the line.” This statement resonates throughout the book, in both the fragmentary shape the poems take and the break within the speaker’s own genealogy. Returning again and again to the character of Michael, Chabitnoy examines this moment of rupture in the linear connection to family and culture. Notably, in the book’s final poem, “Ways to Skin a Fish: A Genealogical Survey,” Chabitnoy ends her genealogical retracing—breaks the line—just before herself:

[Record of Pennsylvania Aleuts ends. Sixth generation missing in surviving

document. No way of assigning number to seventh generation without

disturbing existing order.]

Despite the re-lineation required by the book’s trim, Chabitnoy seems to have resolved any issues satisfactorily. How to Dress a Fish commands space. Not only is the collection long—a physically impressive volume—but the poems, too, spread themselves across those pages. Subverting white space, she draws attention to fragmentation and absence:

It was winter. I was sweating. You and I were in a boat, going back to

Unalaska and my body went cold to spite my discomfort. You can be

wind. You can be feathers. You can be fur or fin and teeth. I am not even

earth. Not even bone. But permafrost in a warming state. Cold, not cold

enough. Porous. Full of holes. Not filled but

disappearing.

At such length a collection risks stagnation, but Chabitnoy slips out of this trap; the book’s three sections cover so much territory the work feels not so much repetitive as sprawling. As images and statements recur—fish skeletons, masks, beginnings—they become imbued with intriguing new meaning thanks to the book’s thematic momentum. Each of the book’s three sections reference these central images through various perspectives, opening new meaning through personal, traditional, and incidental metaphor. While water serves as an image of life, it serves later, in reference presumably to Alaska’s 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, as an image of destruction. And the speaker balances on this fickle bridge as she attempts to reconcile two identities that feel to her, at times, too disparate to commingle.

Translator Emily Wilson has described the Odyssey as “all about finding a beginning: an origin, a starting point, a first. How do you get back to that, and where and what was it again?” As if in response, Chabitnoy opens her book’s second section by writing, “Only the beginning is true / each time.” Like Odysseus, Chabitnoy’s speaker seeks to reconnect a fractured past and return to the island her family called home. Like Telemachus, she looks for some sign in the face of a man from her past who comes to her clad in someone else’s clothes, and she wonders where this person has been who could have helped her grow.

Ultimately, Chabitnoy has crafted a modern odyssey of identity—a sprawling, fractured journey toward a home the speaker doesn’t know if she can ever fully reach: “You can’t throw the fish / back in the water / and expect it to swim—” but she keeps seeking nonetheless. In “[I turned fish]” she asks, “Why should I be the only one / in this place?” Throughout this expansive first book, Chabitnoy draws the reader in and, though the narrative is an individual one, the collection draws power from the fact that its speaker is far from alone in this place and feeling of cultural and genealogical isolation. ![]()

Note: Alutiiq translations here and in Abigail Chabitnoy’s How to Dress a Fish are taken from the Alutiiq Museum’s Alutiiq Word of the Week Archive.

Abigail Chabitnoy is the author of the poetry collection How to Dress a Fish (Wesleyan University Press, 2018). Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Boston Review, Gulf Coast, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Mud City, Nat Brut, Pleiades, Red Ink, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, and Tin House, among others. She has also written reviews for Colorado Review and The Volta Blog. She earned an MFA in poetry at Colorado State University and was a 2016 Peripheral Poets fellow. Chabitnoy is a research associate for a consulting firm specializing in supporting indigenous self-determination.